Should Belmont residents consider a ‘neighborhood conservation district’ model?

By Sharon Vanderslice

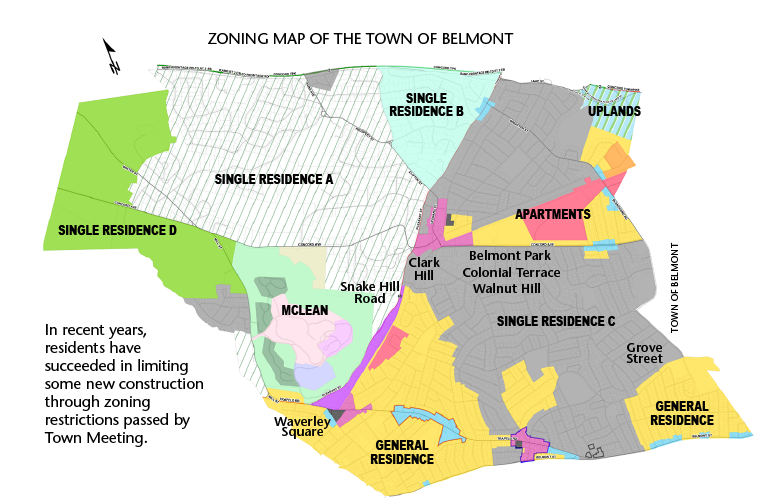

Belmont’s cohesive and walkable neighborhoods, high-quality schools, extensive green space, and proximity to public transportation have made it one of the most desirable places to live in the Greater Boston area. And yet, skyrocketing real estate values and the overdevelopment that tends to accompany them currently threaten the very neighborhoods that have made this “town of homes” so appealing in the first place.

One tool that cities and towns around the country have used to preserve local neighborhoods from inappropriate development is the “neighborhood conservation district” designation. Cities as close as Cambridge or Brookline and as far away as Chapel Hill, North Carolina, or San Antonio, Texas, have identified and preserved local neighborhoods of all sorts using legal restrictions regarding scale, massing, and architectural configuration. Less defined than a historic district but with the ability to be more specific than zoning regulations, the neighborhood conservation district allows the community to determine the character of a given area. Such districts usually place fewer limits on individual homeowners than a typical historic district does. For instance, paint colors and window replacements might not be limited.

- Walnut Hill

- Waverley Square

- Clark Hill

- Belmont Park

- Walnut Hill

- Colonial Terrace

- Waverley Square

- Snake Hill Road

According to Charles Sullivan, executive director of the Cambridge Historical Commission, the city of Cambridge currently has four such conservation districts: Harvard Square, a mixed-use development in the center of the city with 125 separate buildings; Avon Hill, a cohesive single-family residential neighborhood of about 200 homes bounded by Linnaean Street, Raymond Street, Upland Road, and Massachusetts Avenue; Mid-Cambridge, a group of blocks north of Central Square between Prospect and Prescott Streets, comprising 2,200 buildings in total; and Half Crown-Marsh, 190 buildings between Brattle Street and the Charles River.

The town of Brookline currently has two conservation districts: Hancock Village, a development of 789 garden-style townhouse apartments designed by the Olmsted Brothers in the late 1940s; and the Greater Toxteth neighborhood of single-family residences that features an abundance of green space with many mature trees.

These districts are governed by review commissions that must issue Certificates of Appropriateness for new construction or alterations to ensure that such changes are compatible with the existing structures in the neighborhood. A typical review commission has a minimum of five members, including residents of the neighborhood and preservation experts in architectural and landscape design fields.

Candidates for Conservation

Which neighborhoods in Belmont would be ripe for this type of preservation? Lauren Meier, co-chair of the Belmont Historic District Commission, has several to suggest:

- The original Belmont Park development off Concord Avenue, a pre-streetcar subdivision built in the 1890s and encompassing homes primarily in the late Victorian and Shingle style on School, Myrtle, Goden, and Oak Streets.

- The Snake Hill Road development off South Pleasant Street, a cohesive group of mid-20th-century modern homes designed by architect Carl Koch and built between 1940–1941, that has largely maintained its original look.

- Colonial Terrace, an intact and beautiful group of Dutch colonial homes on a cul-de-sac off Orchard Street.

- Clark Hill, a neighborhood of Colonial Revival and Craftsman villas built in the 1870s behind what is now the All Saints Episcopal Church on Common Street.

- The original Walnut Hill, a group of noteworthy Prairie and Garrison Colonial-style houses, built in the early 1900s, on Cedar Road/Hillcrest Road/Fairmont Street/and Highland Road (off Common Street).

Keeping Neighborhoods Affordable

In addition, says Meier, there are neighborhoods in town that are not necessarily historically significant, but which remain more affordable for teachers, firefighters, police officers, other public-sector employees, and citizens of more modest means. She cites the blocks of Garrison Colonial homes near the Grove Street playground (between Grove and School Streets) as one example of a neighborhood that is vulnerable to inappropriate new construction. “I worry about preserving modest housing,” says Meier. “Do we want to become a town of exclusively million-dollar houses?”

Other neighborhoods containing affordable homes include those along Lexington and Waverley Streets in Waverley Square. “But honestly,” says Meier, “any neighborhood could use this as a tool to retain its scale and character.”

Historic Districts vs. Conservation Districts

According to Charles Sullivan of the Cambridge Historical Commission, a neighborhood conservation district (NCD) is “a more flexible solution to specific local issues” than a historic district authorized by Chapter 40C of the Massachusetts General Laws, which takes a one-size-fits-all approach. The Harvard Square NCD in Cambridge, for instance, strictly protects upper stories, while allowing storefronts to be altered without review.

The Half Crown-Marsh NCD guidelines are written to protect highly valued sight lines across backyards in what is a very dense residential neighborhood. Avon Hill, on the other hand, permits more sizable additions on its larger lots but has architectural reviews to ensure that new construction is sympathetic to the neighborhood. In other words, NCD design standards can be tailored to address the concerns of individual neighborhoods. Typically, the NCD process also allows more flexibility in structuring the governing review commission.

Step-by-Step Process

The common first step in establishing NCDs in any municipality is for a consultant or a town commission to conduct a study of local neighborhoods and suggest boundaries for individual districts as well as wording for a potential bylaw. Such a study is usually funded with grants, or in Belmont’s case, could be funded by Community Preservation Act monies.

The second step is drafting an enabling neighborhood conservation district bylaw, which the Historic District Commission, with support from the selectmen, takes to Town Meeting for approval. (The city of Cambridge’s enabling ordinance dates to 1983.) According to former preservation planner Greer Hardwicke of Brookline, her town’s bylaw needed only majority approval of Town Meeting, as opposed to the two-thirds majority needed to initiate a new local historic district. A bylaw of this type might stipulate that a certain number of property owners within a given district would need to give approval before the process could move forward in that neighborhood. (Cambridge initiates the study process with a petition from as few as 10 registered voters.)

A neighborhood conservation district (NCD) is ‘a more flexible solution to specific local issues.’

Third is the appointment of an NCD review commission/s by the Board of Selectmen, which may include residents of said districts as well as one or two members of the Historic District Commission and other preservation experts such as real estate professionals, architects, or landscape designers.

Fourth is the development of design guidelines unique and appropriate for each district by the NCD review commission within the parameters of the enabling legislation. According to Hardwicke, Brookline had block captains who solicited opinions from individual homeowners on this subject.

Anne and Fred Paulsen’s historic home in the Belmont Park neighborhood. (Sara McCabe photo)

Resident Reactions

Former state Representative Anne Paulsen and her husband, Fred, a Town Meeting Member from Precinct 1 who grew up in Belmont, have lived for the past 52 years in a Queen Anne Shingle-style home on School Street that proudly displays a plaque from the Belmont Historical Society. Their home, with its accompanying carriage house, was formerly inhabited by the head of Bartlett Brothers Builders, who constructed many of the houses in the Belmont Park subdivision. Preserving the look and feel of this historic neighborhood is important to them and to other residents of the area.

“I think it’s a great idea,” says Anne of the prospect of designating her neighborhood as a conservation district. Unlike typical historic districts, which focus on architectural details of individual houses, an NCD targets the preservation of streetscapes, ensuring that additions or new construction are compatible with existing homes in the neighborhood. Like a block party, she says, an NCD would be a good forum for bringing residents together to decide how they want their neighborhood to look. The maintenance and replacement of street trees, sustainable lawn care, traffic calming, and architectural repair are all potential topics of this conversation. Fred notes that contractor recommendations from neighbors can be invaluable. While neighborhood conservation districts do not regulate interior reconstruction, Fred says that, for instance, he was able to find a contractor to repair his antique pocket doors by getting a referral from a neighbor with a similar house in the neighborhood.

Steve Pinkerton, a resident of Dalton Road and a member of the Belmont Planning Board, has a different take. In response to creeping mansionization in his own neighborhood between Grove and School Streets, he—along with some of his neighbors—succeeded in proposing amendments to Belmont’s zoning bylaw that limit the height, mass, and setbacks of new construction or additions in Single Residence-C neighborhoods throughout the town. These restrictions, which were passed by Town Meeting in 2016, stipulate that any construction (including a tear-down and rebuild) that increases the gross floor area of a nonconforming structure by more than 30% must apply for a special permit from the Belmont Planning Board.

Less defined than a historic district but with the ability to be more specific than zoning regulations, the neighborhood conservation district allows the community to determine the character of a given area.

In his mind, these amendments obviate the need for conservation district designation. “I think we’ve already done it,” says Pinkerton. The newly amended bylaw prohibits buildings that exceed the average height of other houses in the immediate neighborhood. It requires setbacks compatible with neighboring homes (thus avoiding what he calls a “broken-tooth syndrome” in the streetscape), and it gives the Planning Board the ability to make judgment calls on architectural styles (bungalow vs. colonial, for instance), siding (clapboard vs. shingle), window design (double-hung vs. casement), exterior lighting, street trees, landscaping, and even the placement of ground-mounted outdoor mechanical equipment.

Similar restrictions on single- and two-family houses in General Residence districts were passed in 2014 to assure that new dwellings or additions to preexisting, nonconforming structures are in harmony with the neighborhood. “The goal,” he says, “is not to freeze out improvements, but to do them in a reasonable way, so that new houses and additions don’t come as a shock to the abutters. What you want to avoid is putting 5,000-square-foot houses on 7,000-square-foot lots.” Still, he says, “it’s a fine balance between people’s property rights and the rights of neighbors who have to live with the results.”

Colonial Terrace, by Belmont High student Lily Hoffman Strickler.

Would similar restrictions be welcome in the large-lot Single Residence-A district that is Belmont Hill? How does one ensure that a new house inhabits rather than dominates the surrounding landscape? Slade Street resident Roger Wrubel, who is the director of Belmont’s 90-acre Habitat Education Center and Wildlife Sanctuary on Juniper Road, thinks the town would be wise to take a long-term view. Habitat was recently threatened with the proposed construction of five enormous homes in the backyard of a house on Marsh Street that directly abuts the sanctuary’s land.

While uncertain about the need for conservation districts, Wrubel says, “the town should really consider how Belmont would look in 50 years if you developed up to the limit of what the current zoning bylaw allows, because that is what will happen. Developers will figure out what’s the most money they can make within the current zoning, and that’s what they will build. Large lots will be subdivided unless the zoning changes or land is protected by restriction.”

He personally thinks that the preservation of contiguous open space for wildlife is what’s most important in areas near Habitat, Lone Tree Hill, Rock Meadow, and the Beaver Brook Reservation. “I’m not so concerned about the size of somebody’s lawn on Evergreen Way.”

Lauren Meier of the Historic District Commission (HDC) says that ultimately the support of residents is key to any preservation effort. “The HDC would consider taking on a neighborhood conservation district proposal only if there were substantial support from an individual neighborhood.”

Sharon Vanderslice is a resident of the Pleasant Street Historic District and the founding editor of

the Belmont Citizens Forum Newsletter.

Photos by Sara McCabe

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.