By Meg Muckenhoupt

Where will residents of Belmont and neighboring towns travel in 2030, and how will they get there? Last winter provoked massive debate about the MBTA’s failure to transport hundreds of thousands of commuters to jobs and schools. But in January, before the snows started, Waltham mayor Jeannette McCarthy raised some eyebrows by announcing that she supports building an elevated electric monorail to run from Burlington through Waltham to the Fitchburg/South Acton commuter rail and beyond to Westwood. Will our future hold decrepit, decaying subways and clogged roads, futuristic transport fit for Epcot Center, or some mix of the two?

Last winter’s woes have highlighted just how much Bostonians rely on public transportation, and how fragile that transportation system is. Within the city, mass transit accounts for an average 138,000 trips per weekday into the Boston Business District (Back Bay, the South End, downtown and the Seaport.) Highway travel to that area accounts for 298,000 trips per weekday. The suburban pattern is different, according to State Senator Will Brownsberger and the Center for Transportation Planning Studies (CTPS).

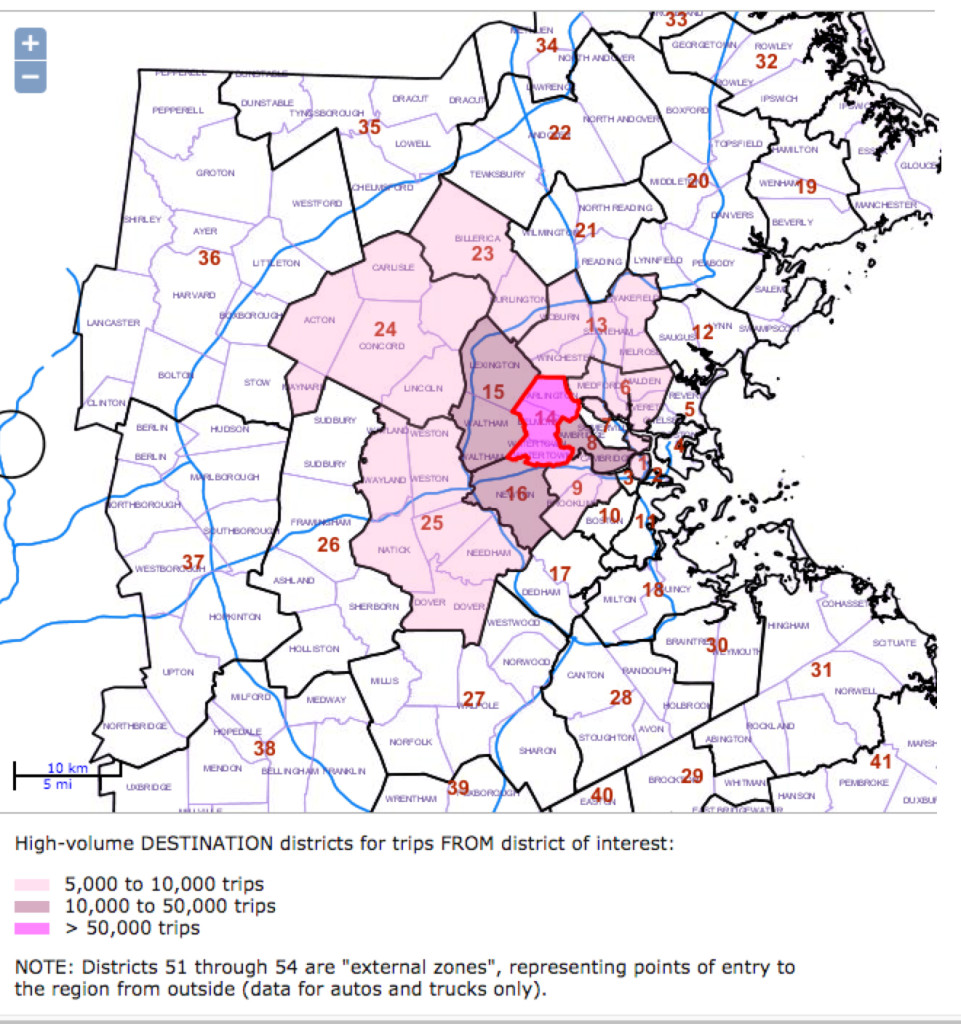

In eastern Massachusetts, a consortium called the Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) conducts the federally required metropolitan transportation-planning process for 101 urban and suburban communities. The CTPS is their professional support staff. The suburban pattern is different.CTPS has analyzed current transportation patterns for greater Boston and made predictions for 2040 based on population growth and other trends. The CTPS has analyzed trips originating in 54 districts of communities in the MPO’s purview.

In District 14, which consists of Arlington, Belmont, and Watertown, about 410,000 trips leave each day, and 355,000 arrive. Of all trips starting in District 14, 77% are made by car, 7% by transit, and 14% by walking. By destination, the vast majority of transit trips (78%) remain within District 14, and Cambridge or Boston. Fewer car trips go to those places, just 60%. Another 14% of trips go to Waltham, Lexington, and Newton, while the remaining 29% scatter among surrounding communities, with no other district getting more than 3% of daily car trips.

Drivers coming from District 15, Waltham and Lexington, span a wider range, with 51% of drivers staying in the district or traveling to Arlington, Belmont, and Watertown, and 25% arriving in towns along Route 128 and Cambridge. All other districts receive less than 3% of trips from Waltham.

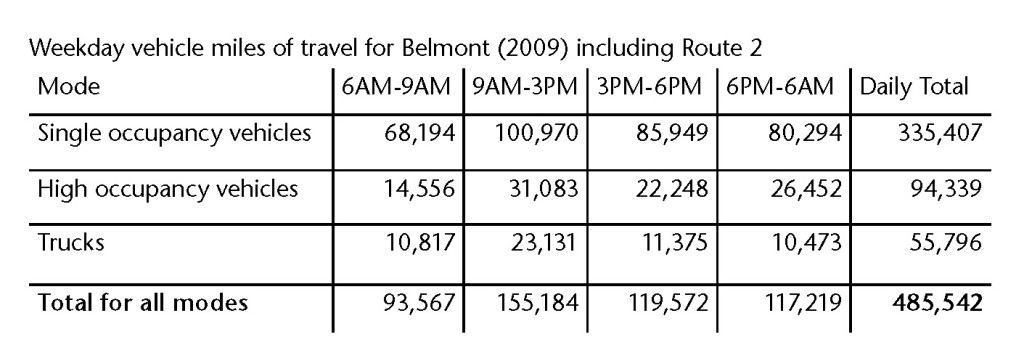

Within Belmont, vehicles are traveling close to 500,000 miles a day, according to the CTPS models (based on 2009 data). That number includes traffic on Route 2.

The Future: Gridlock

Under a “no build” scenario—no new highway lanes or transit—CTPS estimates that the number of cars and transit users entering and leaving District 14 will increase by 12% by 2040, and 16% in District 15.

The Way Forward, a 2013 study by the Massachusetts Department of Transportation, made dire predictions about the Commonwealth’s transportation future: “Without additional investment, however, MassDOT analysis shows that the average driver on the Commonwealth’s congested roads will experience a 23% increase in daily delay between now and 2023—in other words, a 30-minute drive today will require 36.9 minutes 20 years from now. Less than one-third of the estimated demand for public transit in the state will be met. Local roads will also suffer, with deteriorating surfaces and additional delay.”

Regionally, Route 128 has been on the verge of gridlock for years. In 2007, the segment of Route 128 between Lexington and Weston was operating at over 125% of planned capacity, and even minor road accidents could produce massive traffic delays, according to the CTPS. As of 2010, 128,000 employees were commuting to work along Route 128 between Burlington and Weston daily, and 80% of those workers lived in towns outside that Route 128 corridor.

In their 2011 study, Route 128 Central Corridor Plan, the CTPS also predicted that Route 128 traffic would just get worse. “Future job growth, necessary for continued economic vitality, threatens to exacerbate these traffic problems. According to the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC), over the next twenty years. . . population within the corridor will increase by 13,500 and employment will grow by over 8,600 jobs, generating between 100,000 and 200,000 daily auto trips . . . [There are] fifty developments that have been either recently completed or proposed for completion over the next decade, with the potential to create thousands of new jobs. All these developments combined have the potential to increase trips by 77% in addition to existing traffic conditions.”

Solutions

The future doesn’t have to consist of gridlock and disabled trains. The question is, what is the best way to get Massachusetts residents to their daily destinations? How can we transport more people more quickly? Can we stop increasing greenhouse gas emissions, and make sure that Massachusetts residents of all income levels can get where they need to go?

Solutions for the MBTA

MBTA ridership grew at the rate of 1.2% per year between 2000 and 2012, to 1.28 million trips per weekday according to the Urban Land Institute’s 2012 report Hub and Spoke: Core Transit Congestion and The Future of Transit and Development in Greater Boston. But the system is already congested. There are more riders on the Red Line than the system can transport even when there are no catastrophic snowstorms. The Red Line is rated as “over capacity,” which means that peak hour ridership consistently exceeds its trains’ and signals’ collective “crush capacity.” “Crush capacity” is just what it sounds like: calculated as the number of seated passengers plus the number of standees, at 1.5 square feet of floor space per standing passenger.

If ridership growth continues at 1.2%, the MBTA will provide 1.4 million trips per weekday by 2021, leading to more delays and frustration. The Urban Land Institute observed, “Congestion relief has long been a priority for highway spending—it is past time to recognize that addressing congestion is equally important for the transit system.” To reduce congestion, the MBTA needs enough trains, and also the signals to send trains through tunnels more frequently. The MBTA is in the midst of a multiyear project to upgrade Red line signal cables. (For more details on Red Line congestion, see “Housing Boom Comes to North Cambridge,” Belmont Citizens Forum Newsletter, September 2013.)

Solutions for Waltham and Route 128

Build on Existing Transit

No one agency oversees or coordinates all the public and private buses already running on Route 128. Of the 18 different buses and trains, half are privately run by employers, private transit companies, hotels, a residential development, and the Route 128 Business Council, a traffic management agency that uses both public and private funds to provide transit. Coordinating schedules and service areas could make transit to Route 128 faster and more accessible.

One possibility for public-private cooperation is an express bus-on-shoulder line, which would run on the highway shoulder during rush hour to transit hubs. Although bus-on-shoulder lines could provide excellent transit, municipalities must cooperate to ensure that changes to Route 128 access ramps, bridge repair, and road construction do not disrupt service.

Create a New Fitchburg Line/ Route 128 Multimodal Transit Center

The MAPC has proposed a new multi-modal transit center on the Fitchburg Line in Waltham, to be built on the west side of Route 128 somewhere between the Kendall Green and Brandeis/Roberts stops. The idea is to provide a central spot for auto pick-up and drop-off, shuttles, taxis, commuter rail, and pedestrian and bicycle travel, with good access to Route 128, Route 20, Route 117, and the Mass Central Rail Trail bikeway.

In that context, Mayor McCarthy’s monorail idea makes sense. A new transit center with ample parking, bus, bike, and pedestrian access would provide a hub for the monorail. Unfortunately, the MassDOT has not yet begun a planned feasibility study for alternatives for the Route 128 corridor, much less studied the transit center proposal.

Coordinate Mitigation

Many programs and infrastructure changes could ease traffic congestion along Route 128, according to the MAPC’s 2011 Route 128 Central Corridor Plan, including

Coordinating reverse commuting options so that residents can use shuttle services to reach transit hubs;

Eliminating pedestrian and bicycle barriers by ensuring safe access across Route 128 and along roads servicing commercial areas;

Establishing consistent land use policies for commercial zones to encourage a mix of uses, such as retail services (dry cleaning, banking, pharmacy) close to office space so employees do not need their own cars to conduct routine chores;

Developing common site design requirements to bring buildings close to service roads and thereby more amenable to pedestrian and shuttle drop-off access.

Intelligent Transportation

Route 128 is “America’s Technology Highway,” and there is technology available to ease transportation. According to the Route 128 Business Council, “Information collected from loop detectors, cameras, and GPS and cellular data can be used to monitor traffic conditions in real-time. This will allow transportation officials to adjust speed limits, traffic signal timing, and implement ramp metering systems to control roadway volume. ITS technologies are far more cost effective and adaptable than most infrastructure projects, making them a better investment that can be implemented in a much shorter time frame.”

Any solution will require more tax funding. In Massachusetts, income from road-related taxes and fees—the gas tax, license taxes, tolls and such—only covers 59% of the cost of building and maintaining roads in the state. Nor does it begin to cover societal costs of cars—the increased health costs due to air pollution from car exhaust, the drag on the economy from climate change due to greenhouse emissions, and so on. The gas tax, $0.24 per gallon of gasoline, has risen just $0.03 since 1991; thanks to inflation, its purchasing power has been cut in half.

With a few exceptions, transit riders are subsidized too. Although Silver Line SL1 and SL5 buses turn a slight profit, in 2012 the MBTA estimated subsidies per trip for other transit riders range from $.17 to $10.51. The MBTA has eliminated several of the highest-subsidy routes since then. As State Senator Will Brownsberger wrote on his web site, “Buses are the most deeply subsidized mode of transit, with fare revenues covering roughly 25% of operating costs. The several rail components of our transit service — commuter (at 48%), subway (at 61%) and ‘light rail,’ i.e., the Green Line, (at 51%) — cover more of their costs, but their ridership would decline without feeder buses, so it’s hard to tease apart relative cost-efficiency.”

Meg Muckenhoupt is editor of the Belmont Citizens Forum Newsletter

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.