Housing Availability Affects Business Climate

By Vincent Stanton Jr.

Last month the Massachusetts Senate, for the first time in over two decades, passed legislation that would significantly alter state zoning law. The proposed legislation (which will not become law this year as there is not yet a corresponding bill in the House) would superimpose on local zoning a new set of rules designed to encourage greater housing density, particularly near jobs and mass transit.

The new law would reduce the considerable freedom that cities and towns currently have to formulate their own zoning laws in three ways. One is providing financial incentives to municipalities to adopt zoning law changes that comply with state or regional planning agency guidelines, two is reducing the voting threshold required to change municipal zoning laws (e.g., from a two-thirds supermajority of Town Meeting to a simple majority), and three is simply mandating changes in municipalities that do not pass zoning law reforms compliant with the new requirements. The overall effect of the changes would be to provide more “by right” development (discouraging use of the special permit process), to shorten and streamline permitting timelines, and to incentivize “smart growth.”

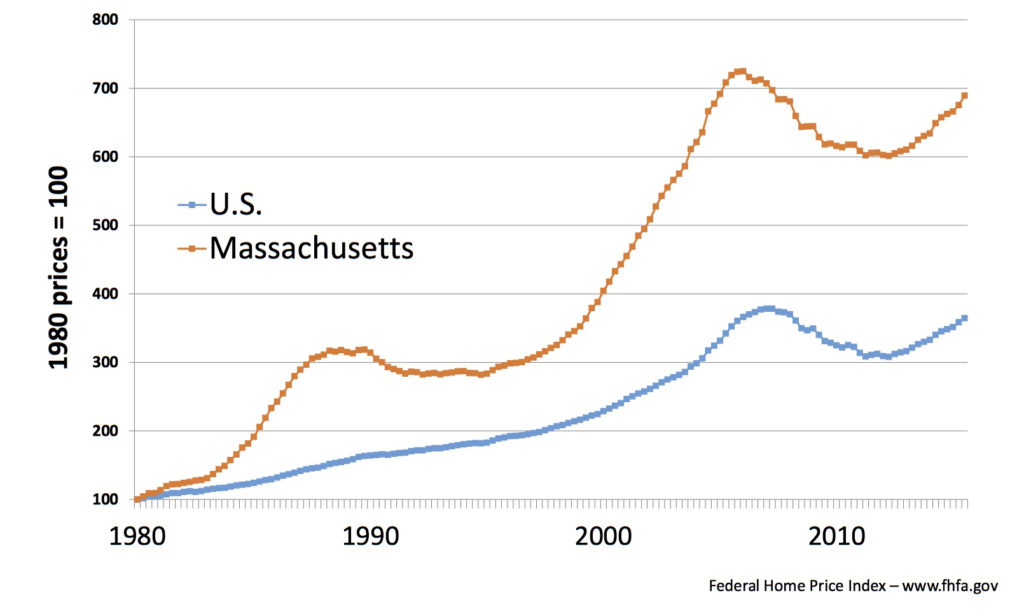

The Massachusetts average housing cost (top line) was the same as the national average in 1980, but has climbed considerably faster since then.

As Senator Will Brownsberger has explained, this was not an easy vote for legislators, as it inserts them into a complex web of hyper-local issues—including the look and feel of a community—about which constituents hold strong feelings. Nonetheless, the Senate was moved to take up and pass the bill by accumulating evidence that the high cost of housing has become a drag on the Massachusetts economy and threatens to become worse.

A June 14 housing forum organized by the Belmont Housing Trust and the Belmont League of Women Voters provided an opportunity to think about the effect these changes in state law would have on Belmont. Clark Ziegler, executive director of the Massachusetts Housing Partnership (MHP), a quasi-public non-profit housing finance agency, explained how other cities at the forefront of the knowledge economy are building affordable housing much faster than Greater Boston, with Austin and Houston leading the pack.

More importantly, Ziegler showed, using US Census data, that growth of the young, educated workforce in the metropolitan Boston area has lagged other innovation centers, despite Boston’s outsized pool of college graduates. From 2008-2012 the young, highly educated workforce grew by 25% in Denver, 17% in Dallas, 16% in Portland, 15% in Seattle and 13% in Austin, TX, while Boston gained only 7%.

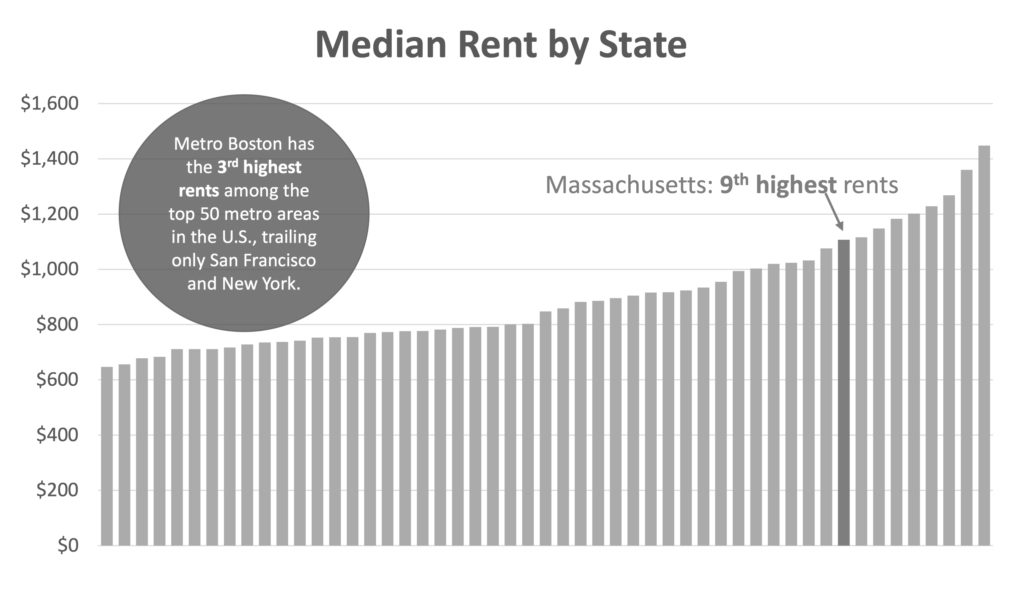

Rent or buy—both are expensive.

Metropolitan Boston has the third highest average rent among the top 50 metro areas that could be considered competitors. Only New York City and the San Francisco/Silicon Valley area are more expensive. In addition, Massachusetts has the ninth highest average rent of all states. As the Boston area competes for talent and manpower, cities and towns need to provide housing that people can afford upon arrival—not after they have climbed the career track.

Today, the average Greater Boston home is worth nearly $700,000, nearly twice the national average of $370,000. . .

In 1980, homes in Greater Boston were about the same average price as those in most other major metropolitan areas. Today, the average Greater Boston home is worth about $700,000, nearly twice the national average of $370,000 for major metropolitan areas (chart on page 1).

Low supply and high demand keep prices high. To support growth and meet demand, the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) estimates that Massachusetts needs 500,000 additional housing units between now and 2040, and 425,000 of them should be in Greater Boston.

As Ziegler and Christopher Oddleifson wrote in the March 30, 2016, online edition of CommonWealth, “Demographic projections from the MAPC show that we need to produce nearly half a million new housing units in Massachusetts by the year 2040 to prevent job losses and achieve only minimal growth. Two-thirds of that projected demand is for multifamily homes, such as townhouses and apartments, and much of it in cities and close suburbs with good access to jobs and transportation.”

How did we get here?

Part of the answer lies in declining housing production. In the 1970s, over 30,000 new homes were built in the state. In the current decade—at the current rate—only an estimated 13,000 units will be built.

Zoning in Massachusetts is regulated mainly by the state’s 351 cities and towns, each serving an average of fewer than 11,000 residents. In many other states, county or regional boards handle zoning. In Massachusetts’ segmented system, as Ziegler and Oddleifson point out, “Resistance to new housing often comes in the form of downzoning—allowing housing development in fewer places or at lower densities than was allowed in the past. It also comes in the form of discretionary zoning codes (as opposed to zoning as-by-right) that make local decision makers especially susceptible to community pressure.”

According to the Massachusetts Housing Partnership, Metro Boston’s high rents put the state at a distinct competitive disadvantage when recruiting talent for the area’s key industries. Source: Mass. Hosing Partnership

Both of those changes have occurred in Belmont: the minimum area required for a buildable lot is greater today compared to decades ago, and increased discretionary power has been granted to the planning board via the special permit process. However, to put those changes in context it should be noted that: 1) Belmont was substantially built out by the 1960s, with the majority of construction since then replacement of existing houses, and 2) the main driver for restrictive zoning changes in Belmont in recent years has not been resistance to new housing per se (after all, the 117-unit Cushing Village was permitted, albeit not yet constructed), but rather concern about the undesirable aesthetic and physical aspects of new houses that are vastly out of scale with the existing neighborhood (“McMansions”).

Housing is up, but only in five cities.

Overall housing production in the Boston metropolitan area was up significantly in 2015, in line with the growth target recommended by MAPC. However, just five municipalities, all in metro Boston’s inner core (Boston, Brookline, Cambridge, Charlestown, Somerville) accounted for 62% of housing production in 2015, according to MHP data. For example, in South Boston’s Waterfront District, in Cambridge across the highway from the Museum of Science, and in Somerville’s Assembly Square, substantial new housing developments opened, all consisting entirely of multifamily units, mostly in high rise buildings.

The housing stock in Belmont (9,760 units in 2015) has been increasing very slowly for decades, but will jump by over 4% in the next few years as the Royal Belmont on Acorn Park Drive fills up (298 units of one-, two-, and three- bedrooms) and Cushing Village (117 units) is finally built. Still, the town will not come close to its 1960 population, which exceeded 30,000 at the peak of the baby boom. Today, the population is about 25,000.

Paradoxically, the McMansions that have triggered zoning bylaw changes in recent years often hold no more residents than their smaller predecessors, suggesting that the real challenge in Belmont is not so much to change buildable lot area or reduce restrictions on house size as it is to identify new locations – with Cushing Village as the obvious model – for substantial housing development.

More affordable homes needed.

The Senate bill would require more affordable and inclusionary units, whose occupants’ income is limited to 80% of the region’s median income, within almost every new development in every municipality. Right now, Belmont, like virtually all the Boston suburbs, lags behind the state requirement that 10% of all housing units be affordable.

Chapter 40B of state law allows developers to override local zoning in towns that do not meet the 10% affordable housing threshhold. Because it was permitted under Chapter 40B, 100% of the 298 units in the Royal Belmont development count toward that 10%; however there is little prospect of the town reaching the 10% level in the foreseeable future. Sen. Brownsberger supports revisiting Chapter 40B as part of zoning law reform, because it provides no incentives to locate new housing near jobs, transit or other infrastructure, or to preserve open space.

The condominiums recently built on Trapelo Road are one example of higher density housing that maintains the local aesthetic. Photo: John DiCocco

Belmont has thought about these problems.

Central aspects of the new legislation were anticipated by the 2010 Belmont Comprehensive Plan developed by the Planning Board, the Comprehensive Planning Committee and the town’s Department of Community Development, with broad community input. In fact, if Belmont were adhering to the 2010 plan, the pending state legislation might have comparatively little effect.

‘As seniors look to downsize but remain in Belmont, there are few opportunities for them to do so on a modest, fixed budget.’

As the 2010 plan notes, the housing crunch affects people who already live in Belmont as well as young people entering the workforce: “As seniors look to downsize but remain in Belmont, there are few opportunities for them to do so on a modest, fixed budget.

Also, young adults and young families looking to buy a first home, or to rent an affordable one, do not have many options in Belmont. Another group in need of housing in Belmont is the workforce. This cohort, both commercial and municipal, requires a range of housing that is not often or easily found in Belmont. Because the town’s housing market is inaccessible to so many groups, Belmont is experiencing a slow, but steady homogenization of the population. This lack of diversity will hurt Belmont in the long run.”

Among the prescriptions in the 2010 plan (See sidebar: Housing Strategies) are recommendations to encourage mixed use development and multifamily or townhouse development in the village centers and corridors; to provide density bonuses for housing development that provides benefits such as historic preservation, shared or underground parking, or air rights development where appropriate; to identify opportunities for higher density mixed-use and multifamily housing as part of a vision for commercial areas, and a host of other ideas that anticipate the senate bill.

What next?

It seems likely that change is coming to Belmont and every neighboring community. Yet, because Senate bill 2311 will not become law this session, there is still time to try to shape the change.

While the Cushing Square Overlay District exemplifies village zoning of the type promoted by the proposed legislation, Belmont residents have not yet had a chance to see how that development works out.

The zoning in Belmont’s other business districts discourages uses that were standard in historic villages. For example, Belmont’s Local Business III districts, do not allow for any residential uses, even though they contain existing mixed-use buildings, which were the dominant historic building form.

However, while Cushing Village may be a model, there are other aspects of the Senate bill about which many Belmont residents would likely object, including the substantial loss of local control over zoning.

While the Senate bill already recognizes that a one-size-fits-all approach is not appropriate (for example regional planning agencies are given an expanded role in drafting model by-laws, and in reviewing municipal applications to become a “certified community”), it might be that more incentives and fewer mandated changes would work as effectively, while politically more palatable.

Dear legislator: ready to act?

Thus one question that could be posed to legislators is whether the balance of carrots and sticks is optimal; whether the same overall increase in housing production might be achieved – although differently distributed – by more carrots and fewer sticks.

One thing seems certain: Belmont’s historical aversion to planning (or at least to taking planning seriously) will be an impediment to achieving optimal outcomes for the town.

Vincent Stanton Jr. is a director of the Belmont Citizens Forum.

The two sidebars below provide more detail on what the town considered in 2010 and what the state may implement in the months to come.

Belmont’s 2010 Strategic Plan for Housing

Following are the recommendations of the 2010 Belmont Comprehensive Plan regarding housing policy, from page 52. See the full plan online at: http://bit.ly/29v4sPV

Promote a walkable/bike-able community of neighborhood villages and connecting corridors with a variety of housing options.

• Encourage mixed use, multifamily, and townhouse development in the village centers and corridors.

• Consider providing density bonuses for housing development that provides benefits such as historic preservation, shared or underground parking, or air rights development where appropriate.

• Propose reductions to on-site parking requirements for housing in village centers that is accessible to public transportation.

Supplement property tax base with renovation and redevelopment.

• Prioritize housing as the reuse alternative for historic buildings located in walking distance to transit and commercial centers.

• Develop design guidelines to shape new development.

• Include representatives of historic preservation, architecture, development, and community-wide residents in a review of land use and building changes.

• Identify opportunities for higher density mixed use and multifamily housing as part of vision for commercial areas.

• Consider allowing flexible dimensional, site plan, and residential uses throughout town for properties that meet design criteria, in order to facilitate preservation of open space and historic features.

Amend zoning to allow/encourage creation of more smaller housing units, including rental housing.

• Consider allowing accessory/in-law apartments.

• Consider allowing three-family structures in areas where they are historically located.

• Consider allowing attached single-family and townhouse development where appropriate.

• Maintain meaningful and economically feasible inclusionary zoning bylaw.

Preserve and upgrade existing housing stock.

• Consider a 90-day demolition delay by-law.

• Consider encouraging building renovation by providing tax relief for improvements compatible with sustainability and historic preservation.

• Consider allowing division of existing homes into multiple units, retaining single family appearance.

• Consider adopting design and dimensional standards that encourage historic preservation.

• Propose design standards that require homes to be in scale with existing neighborhood.

Reduce carbon footprint of new housing construction.

• Consider adopting energy-efficiency building code standards and incentives.

• Consider requiring LEED checklist for all new development.

A Carrot-and-Stick Approach

Senate Bill 2311 is difficult to summarize as it consists of dozens of additions and substitutions to existing law, many consisting of as little as a word or sentence, and seldom more than a few paragraphs. There is no preamble that explains the purpose of all the tweaks. Also, to fully comprehend the proposed changes requires understanding the underlying law, which is extensive. Nonetheless, the carrot-and-stick approach that characterizes the Senate bill can be conveyed in some measure by the following excerpts which (i) provide incentives to “certified communities,” and (ii) make it easier to pass zoning by-laws (which currently require a 2/3 supermajority) that conform to new state guidelines. Read the entire bill at:

https://malegislature.gov/Bills/189/Senate/S2311

Line 13: “The secretary of housing and economic development, …following a public hearing and opportunity for stakeholder feedback, shall develop a municipal opt-in program to advance the state’s economic, environmental and social well-being through enhanced planning for economic growth, land conservation, workforce housing creation and mobility. The program shall include guidelines and criteria to evaluate municipal applications. Applications meeting program guidelines and criteria shall receive status as a certified community. Certified communities shall be entitled to certain privileges and powers and shall be required to provide certain incentives to benefit persons seeking local permits and local land use approvals.”

“The executive office of housing and economic development shall develop guidelines for a city or town to receive status as a certified community. The guidelines shall promote: (i) prompt and predictable permitting of commercial or industrial development within economic development districts that allow for an appropriate amount of development to proceed as of right and within a specific reasonable time; (ii) prompt and predictable permitting of residential development within residential development districts that allow for the appropriate amount of development to proceed as of right and within a specific reasonable time;

(iii) open space residential design for certain zoning districts meeting minimum lot area thresholds for single-family residential development; (iv) low impact development techniques; (v) natural resource protection zoning in areas of significant natural or cultural resources; (vi) development agreement contracts between a municipality and a holder of development rights to express the conditions to which the development will be subject; (vii) consolidated hearings and permitting for large development projects; and (viii) joint applications from 2 or more contiguous municipalities who together meet the goals of the program…”

Line 247: “…provided, however, that if a city or town has failed to meet the minimum requirements …, a zoning ordinance or by-law that is consistent with these requirements shall be adopted by a vote of a simple majority of all members of the town council or … by a vote of a simple majority of town meeting.”

Summary by Vincent Stanton Jr.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.