Habitat Wetlands at Risk

by Vincent Stanton Jr and Roger Wrubel

Notice: the Board of Surveyors meeting originally scheduled for September 19 to discuss the Chiofaro property has been postponed. The town engineer is asking the applicant to first apply for a hearing before the Belmont Conservation Commission to resolve any wetland issues.

In densely settled communities like Belmont, few real estate marketing pitches ring a louder bell than “abuts conservation land.” Indeed, what could be more salable than guaranteed backyard tranquility in perpetuity? Unfortunately, as the perimeter of conservation land becomes densely settled, the value of the land for conservation purposes (animal habitat, a quiet walk, scenic views) is diminished.

The four biggest tracts of conservation land in Belmont are

• Mass Audubon’s Habitat Education Center and Wildlife Sanctuary (90 acres on Belmont Hill);

• Belmont’s Lone Tree Hill reservation, secured via an agreement with McLean Hospital in 1999 (119 acres of open space across Concord Avenue from Habitat, partly town-owned and partly retained by McLean Hospital with conservation restrictions);

• Rock Meadow, Belmont’s western border, owned by the town (70 acres, purchased from McLean Hospital in 1968);

• Beaver Brook North reservation (254 acres, mostly in Lexington and Waltham, maintained by the Massachusetts Division of Conservation and Recreation).

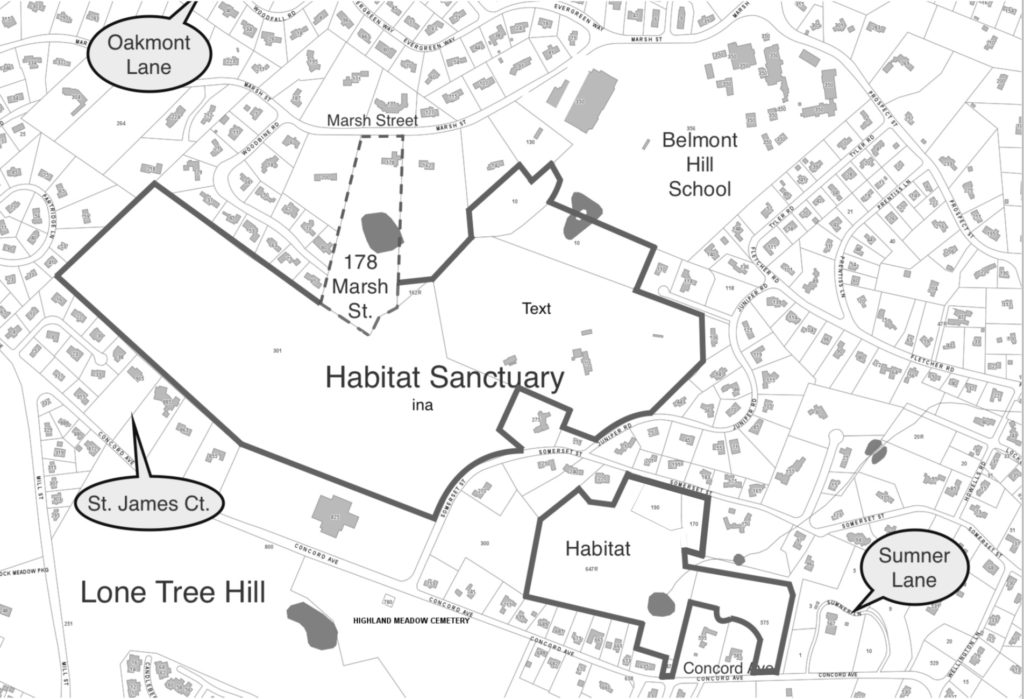

Map 1. The dotted line (left center) bordering on Habitat represents the property where the owner proposes building a new road. Oakmont Lane, St. James Court, and Sumner Lane are other recently built roads on Belmont Hill.

Each of these reservations has historical and natural features. They also have collective value as elements of the 1,000-acre ring of linked open space through Belmont, Lexington, and Waltham known as the Western Greenway (see May/June 2011 BCF Newsletter, page 9).

Habitat is the most vulnerable to envelopment by development because it abuts multiple private properties. . .

Habitat is the most vulnerable to envelopment by development because it abuts multiple private properties; the other three parcels are largely circumscribed by major roads.

Over the past decade, four new houses have been built on what was previously open space adjacent to the Habitat Sanctuary. Five more existing homes bordering the Sanctuary have been torn down and replaced with substantially larger structures. All of that development was allowed “by right” under Belmont’s zoning bylaws. Currently, Belmont resident Don Chiofaro is seeking permission from the Belmont Board of Survey to build a new road through his 6.86-acre property at 178 Marsh Street. The back of the 178 Marsh Street lot borders Habitat Sanctuary for approximately 635 linear feet (See Map 1).

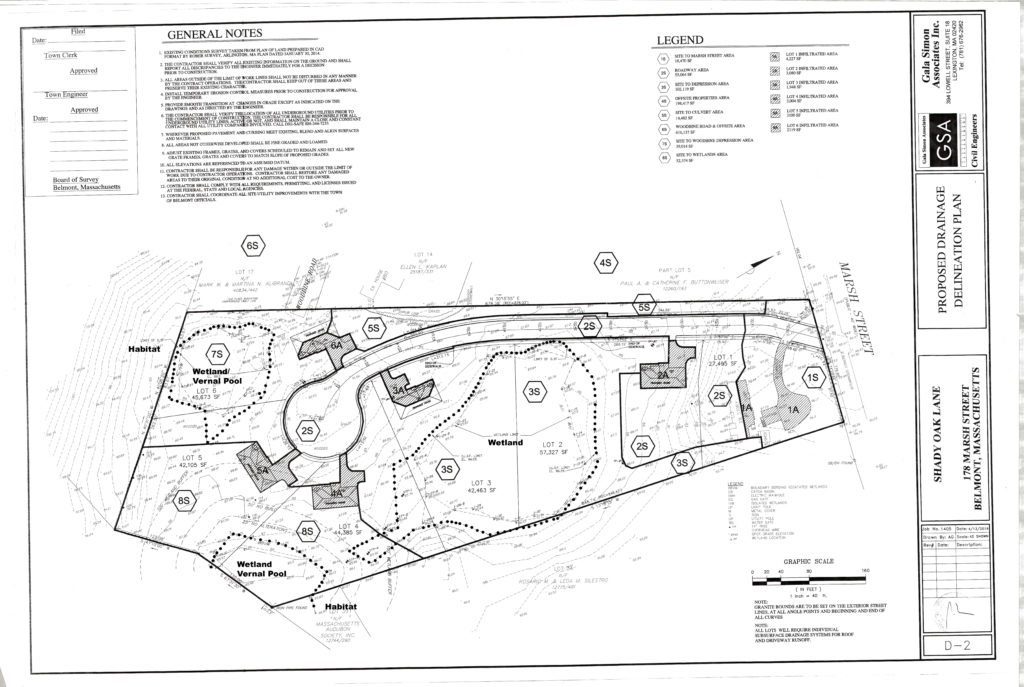

The new road would enable a subdivision into six lots with construction of five new homes. (See Map 2.) The construction of new homes near that border would destroy essential wildlife habitat by removing a relatively rare wet forest that drains into the sanctuary and forms a headwater of the Mystic River. Besides the rare forest, the property contains two certified vernal pools and a large wetland that is likely also a vernal pool. It is a haven for the wildlife many of us observe and enjoy at Habitat. Here, great horned owls and hawks nest; and coyotes, fisher cats, fox, deer, mink, weasels, skunks, raccoons, and terrestrial box turtles roam, feed, and reproduce.

Map 2. The three areas within the property at 178 Marsh Street designated by dotted lines are wetlands (also known as isolated lands subject to flooding (ISLF)) bordering Habitat that face potential damage from the proposed road and homes on the property. ILSF is one of the resource areas in the jurisdiction of the Conservation Commission.

Moreover, because the private open space is adjacent to Habitat’s 90 acres, it has greater conservation value than similar land would as isolated parcels. Bigger is better when it comes to wildlife survival. As prominent conservation biologist Michael Soule is fond of saying, “There are three things you can do to preserve wildlife: habitat, habitat, and habitat.”

“There are three things you can do to preserve wildlife: habitat, habitat, and habitat.”

A decision on the current proposal has implications for other properties abutting conservation lands. Three other properties between 178 Marsh Street and the Belmont Hill School also have limited frontage and large back yards abutting the Audubon sanctuary. Those properties might be developable if new dead-end roads off Marsh Street are allowed.

The loss of open space in Belmont is not confined to properties bordering conservation land. In the last three years, nine multimillion dollar homes have been constructed on the north side of Concord Avenue as it ascends Belmont Hill. That space, facing Cambridge and Boston, used to be grassland surrounding two early 20th-century mansions. Five of the new houses required town approval of a new road (Sumner Lane) to gain sufficient frontage for buildable lots.

Further west on Concord Avenue, on the other side of Belmont Hill, another new road (St. James Court) was recently approved that allows two additional homes in the woods in front of two existing homes at 885 and 905 Concord Avenue. The recent Woodfall Road development of four homes required permitting of a new road (Oakmont Lane) by the Board of Survey.

Belmont residents, in polls and through Belmont’s representative Town Meeting, have repeatedly asserted that they highly value open space. The Working Vision for Belmont adopted by Town Meeting in April 2001 vowed to “protect the beauty and character of our natural settings.” The town’s Comprehensive Plan praises “open spaces and vistas [that] provide connections to the beauty of the natural world.” Indeed, the 1968 Belmont Annual Report, remarking on the town’s purchase of Rock Meadow from McLean Hospital that year, noted, ”the need for preserving this last piece of available land in the congested and overbuilt town of Belmont.”

Belmont residents, in polls and through Belmont’s representative Town Meeting, have repeatedly asserted that they highly value open space.

Chiofaro says “I have no immediate plans for the property. I’m going through the process of meeting the proper boards and hearings just to explore options.” He added, “I wouldn’t do anything that doesn’t fall within the rules and regulations of the conservation committee. I think smart development is good for the community but not all development is smart.” Belmont’s selectmen, who sit as the Board of Survey, have to balance the town’s interest in open space against the economic interests of property owners. While each decision about a new road is made in isolation, the collective impact over time is changing the face of Belmont.

The possibility of substantial changes in Belmont zoning as a result of state law also deserves consideration. (See Sidebar 2).

Vincent Stanton Jr. is a director of the Belmont Citizens Forum. Roger Wrubel has served as director of Mass Audubon’s Habitat Sanctuary for over 16 years.

Sidebar 1: Who has authority to create new streets in Belmont, and how is the decision made?

A buildable lot requires both land and frontage (access from a street). The amount of each varies in Belmont’s five types of residential zoning district. Most of Belmont Hill is zoned Single Residence A (the required lot area is 25,000-square feet and 125 feet of frontage).

For deep lots not accessible from any road, the only way to produce the frontage required for a new buildable lot is to construct a new street. Permission must be obtained from the Belmont Board of Survey, a role filled by the Board of Selectmen. The process is described in a 22-page document titled Rules and Regulations of the Board of Survey.

The rules do not spell out the decision-making process. However, traditionally, applications that fulfill all of the required criteria have been approved. If a proposed new road does not (or cannot) meet all specifications, the petitioner may ask the board to waive certain rule(s). The board may do so “upon an express finding that such action is in the public interest, and is not inconsistent with the intent of these rules.”

The explicit instruction that the “public interest” should inform any board decision about granting a waiver opens up a broader set of considerations than the narrow technical requirements. A new street has implications for public safety (e.g., fire and police resources), schools and other town departments, and the town’s ongoing efforts to improve stormwater drainage systems and preserve open space.

The 2010 Belmont Comprehensive Plan notes, “There is currently limited recognition of private residential property as valuable and integral open space,” and significantly, that conservation of remaining open space is “important for air quality, water quality, wildlife habitats, and natural beauty.” Belmont’s Conservation Commission, which enforces the Massachusetts wetlands laws, also gets to weigh in. 178 Marsh Street includes wetlands identified on town maps. In 2014, the ConCom rejected the categorization of some of the wetlands but was overruled last year by the state Department of Environmental Protection. If the Board of Survey approves the road, the ConCom would be able to regulate how work on some of the new lots is conducted to avoid damage to wetlands.

Sidebar 2: Future development in Belmont

The Massachusetts legislature is considering major changes to statewide zoning law that would compel cities and towns to allow more “by right” housing construction (see July/August 2016 BCF Newsletter). The incentives in the proposed legislation favor housing with an affordable component and located near mass transit, neither of which is achieved by construction of new mansions on Belmont Hill. If the proposed legislation were to become law—a bill passed the Senate but not the House—it might encourage a more vigorous discussion in Belmont about long-term planning issues:

• What types of housing does the town favor?

• Where should new housing be located?

• How can the town preserve the open spaces—both small and large—that contribute to its character, while permitting more housing?

• Is the gradual but continuous and irreversible loss of open space in small pieces compatible with the town’s planning vision?

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.