by Anne-Marie Lambert

Water Quality update: On May 15, 2017, the Belmont Board of Selectmen approved and signed a 2017 EPA Administrative Order for Compliance on Consent with the EPA. This Order includes EPA water sample results through March 30 2016 and makes mandatory the town’s current plan for addressing water pollution. It also includes downstream water quality measurements from Cambridge in 2014 and 2015, and references water samples collected by the town in November 2016. Belmont has also recently posted their IDDE Plan 05-19-2017. The Belmont Media Center link to the May 15, 2017 meeting of the Belmont Board of Selectmen includes a discussion of this order between minute markers 73:44 – 98:20. The Order includes a schedule for addressing the longstanding violation of allowable bacteria counts indicative of illegal discharge of sewage from the municipal stormwater system into local waterways.

–End of update

Belmont used to be known for the purity of water coming from Belmont Spring, the inspiration for a bottled water company (that was eventually bought by Coca-Cola and is now owned by Cott Beverage Company in Canada). You can still buy a bottle labeled “Belmont Springs,” but there’s no way the contents come from Belmont waterways today. As in other densely populated areas around the world, sewage is getting into our brooks and ponds.

Even after millions of dollars of repair work since 2011, the problem remains unsolved. Tests by the Mystic River Watershed Association show we still have a problem. (See the chart below on water quality grades.) Now the town plans to change its approach to finding the sources of water pollution.

A Hidden Problem

Most people don’t notice Belmont pollution. Why? For one thing, people aren’t getting sick: our taps dispense clean water from a mostly gravity-fed system originating at Quabbin Reservoir in western Massachusetts. For another, many Belmont waterways are hidden in conduits or on private property. Clay Pit Pond, with its peeling 30-year-old Health Department warning signs, is visible and accessible. The rest are not: Wellington Brook goes in and out of Clay Pit Pond in underground culverts that start behind the library and end in Cambridge. Little Pond, our largest water body, is only publicly accessible via little-known paths owned by the state’s Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR).

The rest of Little Pond is surrounded by private properties. On Belmont Hill, Winn’s Brook is mostly hidden on private property until just past Belmont Center, where it goes underground to Little Pond. To see Beaver Brook, Atkins Brook, and others, you have to hike through DCR or Audubon conservation lands. Other than Clay Pit Pond, a tranquil but artificial and polluted water body, residents don’t feel connected to our brooks and ponds.

Circles are manholes. The light green and orange lines are sewer pipes and drainpipes. You can explore further at mapsonline.net/belmontma/index. Go to “Layers,” check off “Sewers,” and then enlarge the map until the lines appear. Image by Frank Frazier.

GIS Makes Drains More Visible

How does sewage get into our hidden waterways? Dirty water from our homes and businesses gets flushed into town sewer pipes that pass through a sequence of pumps to push it out to a water treatment plant at Deer Island in Boston Harbor. These town sewer pipes are supposed to keep the sewage separate from the town drainpipes which carry rainwater to our brooks and ponds. You (or a curious young person in your home) can take a look at the sewer and drainpipes near your house by selecting the sewer and drain views in the GIS map system available online through the town’s web site. (See the example map above.)Be sure to enlarge the map enough to see individual streets. Try to find the path from your home to the sewer pump station at Flanders Road, or the path from the nearest catch basin to an outlet to a brook or pond. Note that, unlike nearby Cambridge and Somerville, which started with the challenge of a combined sanitary and storm sewer system, Belmont has always had separate systems.

Mystic River Watershed Water Quality Grades and Compliance Rates – Calendar Year 2015

|

Issue #1: Illicit Connections

The first problem we have in Belmont is that internal sewer pipes in some homes and businesses are connected to town drainpipes instead of town sewer pipes. This illicit connection typically happens when a contractor connects a basement sewer pipe to the wrong town pipe. Without coordinating with the town, it can be difficult to distinguish a sewer pipe from a drainpipe near a home’s foundation. When the nearest sewer pipe is higher than your basement toilet and the nearest drainpipe is not, an illicit connection can also make a basement renovation project cheaper, since no pump system is required. It’s illegal, but it’s hard to detect using the manual dye tests and smoke tests the town currently uses.

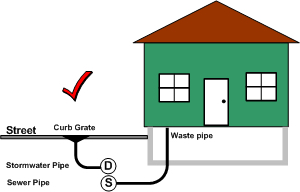

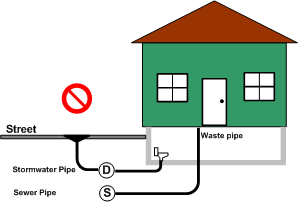

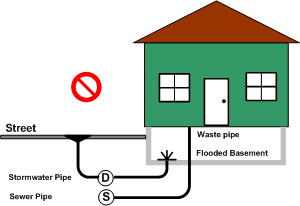

In the three examples below, the top house has the correct connection: house wastewater goes to the town sewer pipe (S). The middle house shows a toilet illegally connected to the town stormwater pipe (D) instead of the town sewer pipe. In the bottom house, it shows the effect of the middle home’s bad connection: during a heavy storm, the stormwater backs up into the house, flooding the basement. Illustrations by Frank Frazier.

Issue #2: Broken Pipes

A second, bigger, problem is that Belmont sewer pipes sometimes crack or collapse. No sensor or alarm alerts us to this underground calamity, but the sewage leaks out with every flush, seeking a path to the lowest point. Sewer pipes are typically in a trench that includes drainpipes. These drainpipes have open joints, where the sewage can enter and find a path to the nearest waterway through an outlet intended for rainwater. Why do town drainpipes have open joints underground? After a storm, groundwater levels rise. In order to provide a path for rising groundwater to get to the nearest waterway instead of into someone’s basement, town engineers leave joints open. If they were sealed, basement flooding would be an even greater problem than it is already. Measuring groundwater levels to understand where this vulnerability is highest seems like an opportunity for modern sensor technologies. Why do sewer pipes crack in the first place? It’s not just that they are old, though that is a factor. It’s also due to poor quality sewer installations in the 1950s. In some neighborhoods, 50-year-old pipes are in more urgent need of repair or relining than 100-year-old pipes.

In some neighborhoods, 50-year-old pipes are in more urgent need of repair or relining than 100-year-old pipes.

Issue #3: High Water Pressure

Water pressure from illegal sewer connections is a major reason sewer pipes crack. When sump pumps, gutters, and other drains are illegally connected to town sewer pipes instead of town drainpipes, heavy rains exert much more water pressure than the sewer pipes were designed to carry. Higher pressure pushes more sewage through existing cracks and creates more cracks. This is difficult to detect with old-fashioned manual inspections. Addressing this issue may involve installing new stormwater drains.

Wellington Brook feeds into Claypit Pond at the west end of the high school driveway, near the baseball field.

Measuring Intermittent Pollution

For all these reasons, the E. coli count in Belmont waterways can get dangerously high for wildlife, pets, and people who come into contact with them. However, E. coli dies off in time. Sewage pollution can get particularly bad for a few days after a major storm, when rain flows in and out of sewer and drainpipes and flushes a lot of sewage into the waterways all at once. Underground cracks or illicit connections can dump sewage into waterways even in dry weather. But if you don’t measure water quality within a few days of a storm or after a recent flush through an illicit connection, you might miss the problem.

Even if you’ve measured a high E. coli count at one outlet at a point in time (e.g., Winn’s Brook’s outlet into Little Pond, October 2016), it can be hard to trace the culprit crack or illicit connection in the miles of town sewer pipes. Unless you are monitoring in multiple locations in real time, it’s usually too late to find the upstream source. Multiple problems could contribute to the high E. coli count—but town engineers don’t know where they are.

Even if you’ve measured a high E. coli count at one outlet, it can be hard to trace the culprit crack or illicit connection in the miles of town sewer pipes.

In addition to E. coli, the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) also tests for the presence of longer-lasting pharmaceuticals in our waterways, such as caffeine, pain relievers like acetaminophen, high blood pressure medication, antidepressants, antibiotics, and other substances found in human waste. EPA testing done in 2011 showed the presence of some of these items as well as E. coli in Winn’s Brook and Wellington Brook. Director of Community Development Glenn Clancy requested a round of water quality measurements at drain outlets in October/November 2016, to be followed by a second round this spring.

Three Years from Detection to Repair

“[Water quality] investigation is not constrained by money and never has been,” Clancy said. “Rather, it’s the nature of the work. You have to find and fix one problem before discovering the next one . . . For all we know, we could be down to one property [left to fix].” Measurements from October 2016 will lead to investigations this spring that may continue through fall before problems are identified. Funds for those repairs are requested from the state Department of Environmental Protection’s Intended Use Plan. The town waits for approval.

[The town] will likely not request proposals until the summer or fall of 2018 for work that will get done in the spring or summer of 2019.

It will likely not request proposals until the summer or fall of 2018 for work that will get done in the spring or summer of 2019. Only once that work is complete can new measurements determine if there’s another problem to investigate. As Clancy remarked in a recent interview, “It’s like peeling layers of an onion: you never know how many other problems are being masked by the one you found until after you fix it.”

A New Approach: Work Inward

Clancy and Belmont’s engineering contractor, Stantec/FST, plan to change the approach to our water pollution challenges. Rather than prioritize inspections of drains nearest a polluted outlet, Clancy has asked Stantec/FST to propose an “outside in” approach to finding and fixing the sewer system’s problems. Instead of starting the inspections with the drains close to where pollution has been detected, he wants to inspect and fix problems on the outer edge of the “catchment area” for a polluted outlet. If done systematically, it becomes easier to declare victory on each section of the system, rather than waiting to see if the most recent repair is the last one and will suddenly give the “all clear” for the whole catchment area.

The goal is to minimize the disruption from digging up and repaving a road more than once.

Stantec/FST is under contract to propose a plan for Belmont to find sources of poor water quality. Stantec/FST would also take into account the age and state of repair of each part of the system. Inspections include monitoring flow meters during storms, as well as dye tests and smoke tests to find illicit connections. Closed-circuit TV (CCTV) inspections of town pipes can also be part of the examination.

Repair-As-You-Go

Historically, the bulk of underground infrastructure repair has been coordinated with the town’s Pavement Management Program, which is mainly focused on road repairs to address poor surface conditions. Based on the age and state of repair of sewer and drainpipes under the roads selected for repair, Clancy typically requests CCTV inspections for cracks so that underground work can be identified before repaving a road. The goal is to minimize the disruption from digging up and repaving a road more than once.

In the past, Clancy has waited to repair problems found by the town’s Illicit Discharge Detection and Elimination (IDDE) plan until they can be bundled with the next year’s pavement management contract. This year, instead of waiting, he plans to get the town Department of Public Works or a contractor to fix them as they are found. That work is likely to include repairing town-owned access lines to each house foundation. Clancy intends to wait for the next construction season only if town or contractor staff are not available, or if significant cost savings would result from bundling it into a larger construction contract next year.

Next Steps

The capital budget for water and sewer repairs in 2017 rose from $300,000 to $500,000 after rate increases were approved in April 2016. The selectmen approved this rate because of the need for more IDDE testing. However, the work required for infrastructure repairs under roads scheduled for repair is estimated at $400,000 this year, leaving only $100,000 for additional water pollution testing and for following through on work identified through the IDDE program.

It is up to the selectmen and Town Meeting to decide whether the town prefers merely to meet regulatory requirements, or to prioritize restoring our ponds and rivers so they are safe for boating or even swimming again. Clancy is hopeful that for 2017 the “outside-in” and “repair-as-you-go” tactics will complement a capital budget process which includes bids that come in lower than estimated. As the budget for 2018 gets finalized, ultimately Clancy relies on elected officials to decide the importance of clean water in our brooks and ponds.

It is up to the selectmen and Town Meeting to decide whether the town prefers merely to meet regulatory requirements, or to prioritize restoring our ponds and rivers so they are safe for boating or even swimming again.

In the recent interview, Clancy appeared open to additional ideas and technologies which will help the town get ahead of this three-year cycle of test, investigate, bid, repair, and test again. While skeptical that it’s feasible, Clancy also appears open to ideas that will help the Belmont selectmen to understand the entirety of the problem of sewage in our waterways. Whatever budget is approved, Clancy expects the town’s engineering contractors to use modern real-time sensor and other technologies to detect and fix Belmont’s water pollution challenges. Regardless of legal technicalities and requirements, Clancy says, “I’m of the mindset we’ve got to get on with it . . . At the end of the day, we have an obligation to solve the problem.”

Anne-Marie Lambert is a director of the Belmont Citizens Forum and cofounder of the Belmont Stormwater Working Group.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.