Leaks and Illegal Connections Create Pollution

by Anne-Marie Lambert

After months of negotiation with the EPA, on May 15 the Belmont Board of Selectmen approved and signed a 2017 EPA Administrative Order for Compliance on Consent. This enforcement action makes mandatory a negotiated plan for addressing our illegal discharge of sewage into the Mystic River watershed. It requires the town to investigate and remove all pollution within five years, a daunting task.

The likely sources are leaks and illegal connections in over 50 miles of Belmont’s 76 miles of street drains, as well as in over 50 miles of lateral drains connecting homes and other buildings with the street drains. It sure would be helpful—and cost effective—if homeowners who know or suspect they have an illegal connection would fix it.

Responsible action by homeowners means the town could avoid spending our tax dollars on the expensive detective work that’s needed to find illegal connections. It could instead spend its resources on actually fixing the problem. In many cases, the town will cover the repair work right up to the foundation.

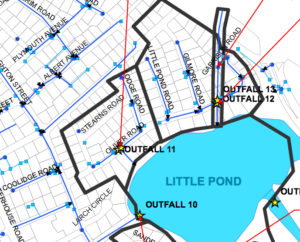

Figure 1. Drainage to Little Pond from outfalls 11, 11A (right next to 11) and 12 (from the IDDE Plan street map). To learn more, visit http://bit.ly/2u2jWXm.

On May 19, the town submitted a detailed document, known as an “IDDE Plan” (Illegal Discharge Detection and Elimination) for review and approval by the EPA. This plan is posted on the town website and includes a map showing the 17 places (known as “outfalls”) where Belmont’s drains empty stormwater into water bodies flowing into the Mystic River. The consent order requires that the town complete the search for pollution sources discharging through the two highest volume outfalls, Winn’s Brook and Wellington Brook, by November 1, 2017. The drains into Winn’s Brook (outfall #10) include more than 175 drain manholes.

The underground Winn’s Brook culvert then drains into Little Pond, collecting stormwater from as far away as Marsh Street, Village Hill Road, and Rutledge Road on Belmont Hill, as well as from Belmont Center and along Channing Road by the railroad tracks. The drains into Wellington Brook (outfall #8) include about 400 drain manholes. Wellington Brook is larger and drains into Blair Pond off Brighton Street, collecting stormwater from as far away as Old Concord Road on Belmont Hill, Trapelo Road just before Star Market near Grant Road, Belmont Street between Lexington and Common Streets, and neighborhoods around the Chenery Middle School.

Very high levels of E. coli have been detected at these outfalls during both wet and dry weather.

The town proposes prioritizing investigation of the areas draining into three low-volume outfalls that flow directly into Little Pond; these are independent of Winn’s Brook and Wellington Brook. Figure 1 on page 10 shows the areas—11, 11A, and 12—that drain into these outfalls. The table below summarizes the level of pollution and the key “suspects.” It’s instructive to consider the detective work involved in trying to find the sources of pollution even in the relatively tiny areas associated with these outfalls.

Phase 1: Sampling/Storm Drain Inspections near Oliver Road

Very high levels of E. coli have been detected at these outfalls during both wet and dry weather. Following an approach recommended by the EPA, the proposed first phase of investigation will be for town contractors to identify strategic junctions at the outer edges of this portion of the drain system, then to work with the Department of Public Works (DPW) to lift the manhole above each selected junction, and place sandbags to catch dry weather flow. Stormwater drains should not contain any flow during dry weather.

| Outfall Number |

E. coli (MPN/100 ml* in dry weather sample) |

Phase 1: Select & inspect drain manholes |

Phase 2: Select |

Phase 2B: Inspect home connections2 |

| 11 & 11A |

11: >10,000 ml 11A: 8,600 ml |

Total: about 6 drain manholes |

Staunton rd., Oliver Rd (2-71), Stearns Rd., Lodge Rd., Cross St. (303) |

About 40 houses, of which 20 are near a street drain |

| 12 | 10,000 ml | Total: about 10 drain manholes |

Oliver Rd. (75-140), Gilmore Rd., Little Pond Rd., Cross St. (321-346), Lake St. (244-300) |

About 60 houses, of which 45 are near a street drain |

*EPA’s threshold for E. coli in Class A or B waters (internal waters) is 235 coliform-forming units/100 milliliters (cfu/100 ml). Sample measurements are sometimes designated in Most Probable Number (MPN) [of coliform-forming units].

If, after 24 hours, the area is still dry, they move on to the next junction closer to the outfall. If they notice liquid or other discharge coming from upstream of the sandbags, they take a sample and send it to a lab to test for E. coli and other evidence of sewage that may not be obvious from its odor or appearance. If the test is negative, the liquid may be just groundwater seeping in through open joints in the drain system. If the test is positive, they move to Phase 2. This outside-in approach is based on the experience of the Boston Water and Sewer Commission1, and assumes residents are at home when the testing is done. The consent order stipulates that testing be done during morning hours.

Phase 2: Dyed-water Testing

Having identified areas suitable for more intensive investigation, the town proposes examinations under streets where they know a sewer pipe is located above a storm drain. Town staff and contractors deposit dyed water into the sewer pipe, then check to see if the dye stays in the sewer system as it should, or shows up in the downstream storm drain. If dye traces are detected in the storm drain, they know there is a problem with the main line under the street.

Presumably the town will schedule repairs of any leaks or collapsed sewer or stormwater drains they find under the streets.

If the dye test doesn’t find any problems in the main lines under the streets, similar tests are used to look for illegal connections or broken lateral lines between each of the homes near a street drain. They start knocking on homeowners’ doors to ask permission to deposit a safe dye into a sink or toilet, so they can check whether the dye shows up in the storm drain system. If traces of dye are found downstream, then they know there is a problem with the lateral connection between a house and the mainline. Even in these low-volume outfalls, there are about 65 homes near a storm drain. That’s a lot of doors to knock on during summer vacation season.

Phase 3: Closed Circuit Televised (CCTV) Inspections

The next step the town “detectives” propose is to send a special camera down the sewer and storm drains to look for leaks and collapsed pipes where there is evidence of contamination. They also propose inspecting any lateral connections identified in Phase 2. CCTV inspection is even more expensive than dye testing, as it requires that the drains first be cleaned, a trained crew operate the expensive equipment, and a police detail be used in cases where traffic has to be rerouted to ensure worker safety.

While it’s not stated explicitly in the IDDE plan, during Phase 3, presumably the town will schedule repairs of any leaks or collapsed sewer or stormwater drains they find under the streets. Depending on the scope of the damage, this may involve relining a section of pipe between two manholes, or possibly going out to bid for the job of digging up the street to replace the pipe.

Phase 4: Illicit Connection Removal

When an illicit connection from an individual home is identified, the town will use information from CCTV and an internal plumbing inspection to determine the appropriate rehabilitation step. The 2017 EPA Administrative Order for Compliance on Consent requires that the town remove illicit discharges within 60 days of verification, or submit an alternative schedule for EPA approval. If an illicit discharge is the responsibility of a property owner, the town must:

• Notify the property owner in writing within 30 days.

• Send a letter within 60 days if the illicit discharge is not yet eliminated, citing the owner’s responsibility to remove the illicit discharge as expeditiously as possible; the legal consequences of failing to comply; and the range of available enforcement options from penalties to terminating service.

• Send a second letter within 90 days if the illicit discharge is not yet eliminated, describing the commencement of fines to be included in the owner’s water and sewer bill. This letter must describe how the fines will escalate until the illicit discharge is removed and enumerate further actions the town may take.

• Prosecute property owners who do not remove their illicit connections.

• Report to the EPA on each legal action and step taken to escalate enforcement.

The Task Ahead

When I think about the effort it will take just to find the sources of pollution flowing into a few very low-volume outfalls, I wonder how we could possibly meet a requirement to find and eliminate all sources of pollution in the large-volume Winn’s Brook and Wellington outfalls within five years.

I wonder how we could possibly meet a requirement to find and eliminate all sources of pollution in the large-volume Winn’s Brook and Wellington outfalls within five years.

Together these two large-volume outfalls drain an area about 100 times larger than that associated with the three most-polluted, low-volume outfalls (see Figure 1 on page 10). Town staff seems focused on matching the number of inspections to a manageable re-construction process within the Pavement Management Program. The EPA regulations also seem to discourage detecting more problems than we can fix at once.

Nonetheless, with the “outside-in” approach to inspection, I’m hopeful more detective work can happen in parallel throughout the watershed, and that modern sensor technologies become part of the plan.

As the town waits for the EPA to review their proposed IDDE plan, pollution continues to flow out of Belmont with each flush from an illicit connection and with each rain storm flowing in and out of our broken pipes.

The selectmen and town staff seem to think we’re moving as fast as possible and claim not to know what they would do with more funding. The town and EPA are working together to clean up our waterways. Take a look at what they posted on the town website, and let them know if you have knowledge or ideas which might further accelerate the cleanup.

Anne-Marie Lambert is a board member of Belmont Citizens Forum.

1. Boston Water & Sewer Commission 2004, “A Systematic Methodology for Identification and Remediation of Illegal Connections,” 2003 Stormwater Report, Ch. 2.1.

2. Streets and house counts estimated by correlating street names and addresses in Figure 1 Sub-catchment Area Locations, in Town of Belmont IDDE Plan Memo dated May 19, 2017, with those in Google maps.

References:

Consent Order also includes downstream water quality measurements from Cambridge in 2014 and 2015, and references water samples collected by the town in November 2016. http://m.belmont-ma.gov/sites/belmontma/files/u146/belmont_sampling_results.pdf

The Belmont Media Center link to the May 15, 2017, meeting of the Belmont Board of Selectmen includes a discussion of this order between minute markers 73:44–98:20.http://www.belmontmedia.org/watch/board-selectmen-051517

The order includes a schedule for addressing the longstanding violation of allowable bacteria counts indicative of illegal discharge of sewage from the municipal stormwater system into local waterways.

The order includes EPA water sample results through March 30, 2016, along with others.http://www.belmont-ma.gov/sites/belmontma/files/u146/epa_belmont_data_aoc.pdf

In addition,there have been multiple stories in recent issues of this newsletter:

“Cleaning Up Belmont’s Polluted Waterways,” May/June 2017

“Belmont Driveways Can Soak Up Rainwater,” January/February 2016

“How to Measure Belmont’s Stormwater,” November/December 2015

“EPA Proposes Expanded Stormwater Permit,” and “Stormwater Forum Details Flooding, Pollution,” November/December 2015

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.