By Michael Chesson

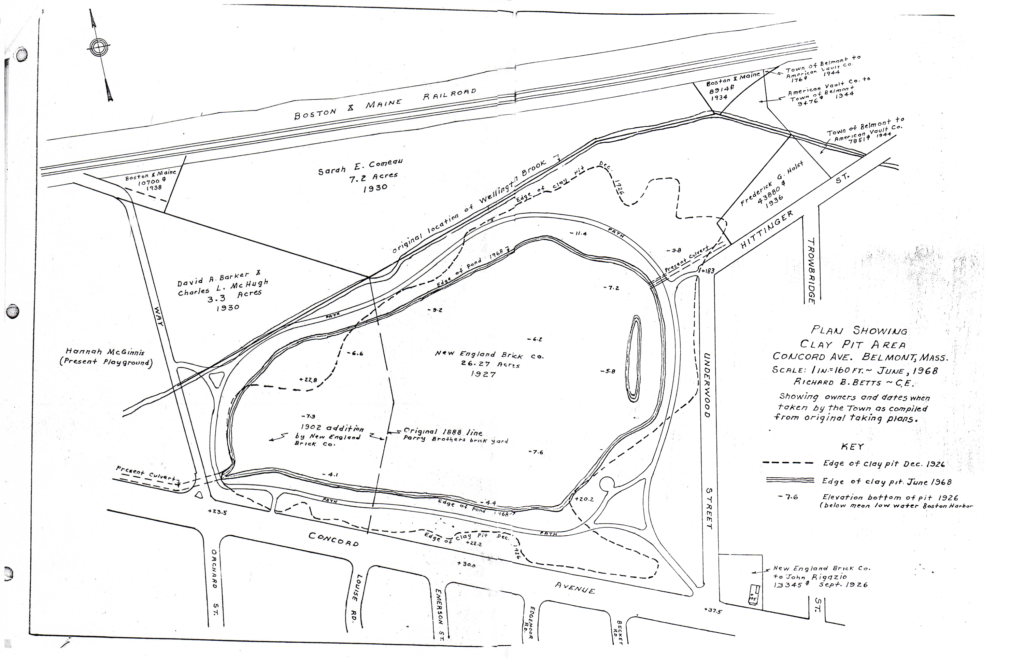

Clay Pit Pond on Concord Avenue was once the site of Belmont’s largest industrial enterprise, a brickyard run by John H. and Robert A. Parry. The brothers bought 20¾ acres of land in 1888 on Concord Avenue and Underwood Street, with its valuable blue clay that turned an attractive reddish color when fired, and their yard produced 200,000 bricks a week.

Just as the oil, steel, and railroad industries consolidated, the Parry brothers’ business in 1900 merged with the New England Brick Company, which owned three dozen other brickyards in the region. The firm installed new dryers, increasing output to 300,000 bricks a week, or 15 million bricks a year. At the west end of the Belmont operation, 75 men lived in a large brick boarding house.

Color print of some of the buildings of the Clay Pit brick company, possibly a water color by local artist Nelson Chase. Courtesy of Michael Chesson/Belmont Public Library.

The yard also featured an engine house, brick sheds, steam boiler, and a railroad siding. In 1902, the company bought six more acres to the west along Concord Avenue that reached as far as the Alexander Avenue extension.

Detail of Belmont map showing the pre-1932 route of Wellington Brook. The scan of an 1889 atlas shows the course of Wellington Brook flowing NE across McGinness and Patterson properties, and north of the Parry brothers brickyard and the clay pit that became Clay Pit Pond. Image courtesy of Michael Chesson/ Belmont Public Library.

When the seam of famous blue clay ran out, the brothers abandoned the site in 1926, along with its heavy equipment. The pit filled with rainwater, only partly submerging a one-and-a-quarter-cubic-yard power shovel made in Marion, Ohio. The selectmen asked Bill Tompson, street superintendent in 1927, how the machine could be destroyed. He replied that Ed Looney, head of the water department, would blow it up with his dynamite. Perhaps cooler heads prevailed. Thirty years later, a 1926 photo of the Clay Pit shovel, by then completely underwater, won the prize in the Marion Power Shovel Company contest for the oldest of its shovels in existence. The machine was judged to date from the company’s beginnings as the Marion Steam Shovel Company in 1884.

An 1884 Marion power shovel, said to have been taken in 1926 after Clay Pit closed. This photo won a prize from the Marion Company for being a picture of its oldest shovel. Image courtesy of Michael Chesson/ Belmont Public Library.

In 1932, Belmont converted the pit to a pond by digging an outlet culvert at its east end through which water exited underground to Blair Pond and Little River in Cambridge. Wellington Brook, which for generations had flowed between the railroad tracks and the site of the current high school, was diverted into Clay Pit in 1933. The brook drains two-thirds of Belmont’s watershed, all the way from the Watertown line at the intersections of White and Lexington Streets with Belmont Street, through Pequossette Park, the Town Field and beyond, including parts of Waverley Square, Cushing Square, and most of Belmont Center. Nothing was done to protect the new pond, which became a receptacle for whatever washed off streets and gutters into storm sewers.

Evidence of pollution in Clay Pit Pond piled up. A woman wrote to the Belmont Herald in 1970 about the oily slick she’d seen in the pond, along with a dead possum and a live rat. The editor joked that she must be new to town: The pond was not polluted, it just had never been especially clean. Articles in the Belmont Herald in 1980 said botulism in the pond killed 30 ducks. In 2003, 1,000 gallons of fuel oil from the Burbank School leaked into Clay Pit Pond.

In 1995, the Belmont Conservation Commission asked the Massachusetts Health Department to test fish in Clay Pit. Results showed a high level of chlordane, a carcinogenic pesticide banned nationally in 1983, which decomposes slowly and builds up in wildlife. Further testing indicated the most polluted water was closest to the Wellington outlet, just past Concord Avenue. High E. coli levels washed into Clay Pit from raw sewage in our stormwater, and from dog waste left by owners on the path around the pond. The Belmontonian reported a similar story again in 2016.

Tom Walsh, the Belmont tree warden, has told the Shade Tree Committee about the time he was working in the pond near the Wellington Brook outlet, and his skin started to burn. He stayed in the water until he finished the job, then sought medical attention for the painful rash on his legs.

For decades our stormwater has been a health hazard for our neighbors in Cambridge, Arlington, and Medford. It contributes significantly to pollution of the Mystic River. Some progress has been made recently, after Belmont signed an Administrative Order for Compliance on Consent with the EPA on May 15, 2017. Town Engineer Glenn Clancy has worked for several years to locate illicit sewer hookups and leaking pipes. He believes Belmont will meet the minimum EPA water quality standards by a 2022 deadline set by the consent order. If Belmont fails to meet the standard, however, the town could face a huge fine.

Besides sewage, another major pollutant at Clay Pit is pesticide and fertilizer runoff from our lawns, parks, and playing fields. Roundup, other pesticides, and many harmful fertilizers inevitably end up in our stormwater, and then Clay Pit and beyond. Some of these are carcinogenic. Some contamination stays local: Clay Pit Pond water has been used to irrigate the fields near the high school.

Most states, including Massachusetts, forbid municipalities from setting their own pesticide policies for private property. Despite this, more than 140 municipalities nationwide have passed ordinances against pesticide use, including Portland, Ogunquit, and other towns in Maine; Dover and Portsmouth, NH; major cities like Tucson, AZ, Boulder, CO, and Miami, FL; and dozens of locales in California. Most of these measures apply to public property like parks and playing fields. Locally, the Rose Kennedy Greenway, Harvard University, and Mount Auburn Cemetery all ban the use of pesticides. Our town could join them.

Additional cleanup measures are possible. Belmont could drain Clay Pit Pond, test and dredge any toxic muck that is found, and perhaps deepen the pond, to convert it into a stormwater retention area. Or, lowering its water level before a big storm could prevent it from overflowing, as it did in August 1955 and March 2010. Building a dam at the outlet culvert beneath Underwood Street could alleviate flooding, by allowing a storm surge from downstream to back up into the pond, instead of toward Blanchard Road and Cambridge.

Belmont has the Quabbin Reservoir for drinking, and the new Underwood Pool for swimming three months each year. Could Clay Pit Pond somehow similarly contribute? Carp live in the polluted pond and stir up sediment. If the water were cleaned, native bass and trout might thrive and replace the carp. Imagine it: Clay Pit as the site of Belmont’s annual spring fishing tournament and a good year-round fishing hole. A relic of our industrial past could help stormwater control and climate sustainability. It would also be a thing of beauty, as clean as it only now appears to be.

The East Walk just after construction, June 1939. Courtesy of Michael Chesson/ Belmont Public Library.

Thank you to Anne-Marie Lambert and Fred Paulsen for fostering my interest in Clay Pit Pond and its pollution from our stormwater and lawn runoff, and to Viktoria Haase, president of the Belmont Historical Society. Haase was instrumental to this research, especially in navigating the resources in the Claflin Room of Belmont library.

Michael Chesson has lived in Belmont since June 1988. He is a Town Meeting Member and has served on the Historic District Commission for the past 4+ years. He is on the board and vice president of the Belmont Historical Society.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.