By Meg Muckenhoupt

With 12 townhouses proposed for a half-acre site at 91 Beatrice Circle, Belmont is buzzing with questions about how a developer can suggest such a dense development. The answers—because this question does not have a single, simple answer—have to do with a law known as Chapter 40B, aka the “Massachusetts Comprehensive Permit Law,” the legal definition of “affordable housing,” and how Belmont has developed up to now.

What is Chapter 40B?

Chapter 40B is a state law that was passed in 1969 to increase the supply of affordable housing in Massachusetts. As the Department of Housing and Community Development (DCHD) website states, “Chapter 40B is a state statute, which enables local Zoning Boards of Appeals to approve affordable housing developments under flexible rules if at least 20-25% of the units have long-term affordability restrictions.” Those “flexible rules” mean that developers can override local zoning and build much more densely than is normally allowed under local zoning.

Of course, those “flexible rules” only apply if the developer offers enough affordable units. The way Chapter 40B counts affordable housing has had a profound effect on development in communities throughout Massachusetts.

What is Affordable Housing?

Most homeowners and renters think a property is affordable if they can live there for a price they’re willing to pay for it. A lawyer making $500,000 a year has a different definition of “affordable” than a sales rep making $50,000 a year.

By contrast, the state has a very specific definition of “affordable housing,” as outlined in Chapter 40B. There are two parts to it: a calculation based on the local median income and legal restrictions on a property’s future sales, known as deed riders.

Median Income and Housing Costs

As stated in the Belmont Housing Trust’s 2018 Belmont’s Housing Future: Housing Production Plan, affordable housing “has a rent or mortgage cost set at no more than 30% of the income of households earning less than 80% of the Area Median Income and has a long-term deed restriction that insures the income and cost restrictions.”

As of June 2020, the Area Median Income for the area including Belmont was $119,000, according to the federal department of Housing and Urban Development. A household earning 80% of that income would bring home $92,500 per year and should pay no more than $28,560 for housing, or $2,380 per month. (The amount actually used for housing calculations depends on the number of people in a household.)

For renters, that $2,380 is supposed to cover rent and utilities. For people seeking to buy affordable homes, that $2,380 is supposed to cover “all payments made towards the principal and interest of any mortgages placed on the unit, property taxes, and insurance, as well as a homeownership, neighborhood association, or condominium fee,” according to DHCD. The average tax bill in Belmont is now $14,135 per year, according to the Belmontian, or $1,177 per month, which doesn’t leave much of that $2,380 for paying a mortgage.

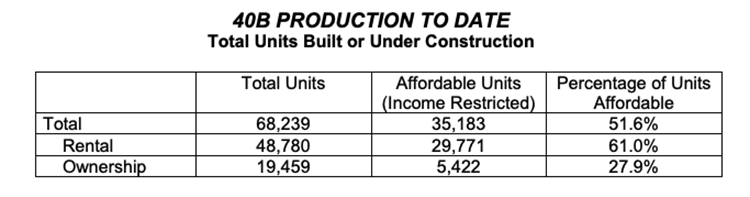

Massachusetts Chapter 40B production as of 2016. Source: www.mhp.net/writable/resources/documents/Municipal-role-in-Ch.-40B.pdf

Deed Riders

To count as affordable housing, homes, condos, and apartments need to have deed riders, clauses which specify that the unit will stay affordable for at least 30 years after construction for new units and 15 years for remodeled units that are being put under restrictions for the first time. They specify a maximum sales price or rent using the same formula as the affordability calculation above: no more than 30% of the pay of a household earning 80% of the Area Median Income.

The need for a deed rider to be considered “affordable housing” is hard for many people to understand. It doesn’t matter if half the housing in Belmont costs only $1,000 a month. If there isn’t any income test to make sure that people in need get that housing, and the price of that housing could change at time, it doesn’t count as affordable housing. The state does not consider privately owned housing affordable housing unless there is a deed rider that guarantees it will be affordable in the future.

When is an Affordable Unit Not Affordable?

Chapter 40B intended to increase affordable housing in Massachusetts, and it has. According to MassHousing, a quasi-public agency that helps finance affordable housing, roughly 70,000 housing units have been produced under Chapter 40B, and 35,000 of those units are restricted to households making less than 80% of the area median income.

You might think it’s strange that only half the units built under Chapter 40B are affordable by the standard state definition. That discrepancy is due to a few quirks in Chapter 40B’s methods of counting affordable housing.

First of all, some affordable housing built before 1990 has outlasted deed riders or mortgages that restricted their sales price to affordable standards, so that the affordable housing is an “expiring use.” State and local authorities have been buying thousands of affordable housing rental units built in the 1970s with 40-year mortgages in recent years; Lexington bought five rental units in 2017 to deal with their expiring use.

Secondly, Chapter 40B doesn’t count all units the same way. First, a development can qualify as a Chapter 40B project in two ways:

- 25% of units must cost no more than 30% of the income of a household earning 80% of the area median income, the $2,380 listed above; or

- 20% of units must cost no more than 30% of the income of a household earning 50% of the area median income, or $1,490 per month in Belmont.

But there’s a catch. Rental units aren’t counted the same way ownership units—homes and condos—are counted. Under Chapter 40B, if you build a rental development with the required percentage of units, all the rental units count as affordable. If you build a condo development of 20 condos with 5 affordable units, you have contributed 5 affordable housing units to your town’s inventory. If you build 20 rental apartments including 5 affordable units, you will contribute 20 affordable units to your town’s affordable housing inventory.

One reason for counting market-rate apartments as affordable is that Boston has a general housing shortage, not just an affordable housing shortage. The Metropolitan Area Planning Council estimates that the greater Boston region will need 400,000 new housing units by 2040 if the region continues its economic growth.

Safe Harbors from Chapter 40B

The reason it’s important to count the amount of affordable housing in town is that it gives communities a way to measure their progress in making it easier to live here and that it gives them a way to stop future Chapter 40B developments.

The point of Chapter 40B is to increase affordable housing, not to make every town inside Route 128 look like Kendall Square, so there are two ways to become a “safe harbor,” i.e., a community that can deny or put conditions on Chapter 40B developments.

First, communities can meet one of three minimum criteria for housing:

Affordable housing units make up at least 10% of the community’s housing stock. This housing is also called the subsidized housing inventory, or SHI. As of 2018, 65 Massachusetts communities had reached this goal according to DHCD.

Have affordable housing built on 1.5% of the total land area. As of 2018, 11 communities had asserted that they qualified for this safe harbor designation, including Arlington and Waltham. A DHCD publication states, “In each case, DHCD reviewed facts and determined that the community had not achieved the 1.5%.”

Affordable housing is being built on at least 0.3% or 10 acres of the community’s land that year.

The other way that communities can become a safe harbor from Chapter 40B is to create and act on a housing production plan (HPP), as certified by DHCD. The Belmont Housing Trust’s Housing Production Plan fulfills this purpose, but the town still needs to actually produce housing to reach safe harbor.

If a community increases the number of affordable units by 0.5% in a year, the town is granted safe-harbor status for one year. If they build 1% units, they get a two-year safe-harbor status. Since 2003, more than 50 communities have earned safe harbor status for at least a year, including Arlington and Watertown—but not Belmont.

Even if they’re not safe harbors, communities can reject projects that are simply too big. Communities with more than 7,500 housing units can deny Chapter 40B projects with more than 300 units. Belmont had under 10,000 housing units (9,710) as of 2018—which means that anything up to 299 units is fair game as far as Chapter 40B developers are concerned.

Communities can still approve Chapter 40B developments once they reach safe harbor or invite developers to work with the town to build Chapter 40B developments to increase the supply of affordable housing. The point is that safe-harbor communities have a choice.

Belmont’s Current Chapter 40B Project: 91 Beatrice Circle

A depiction of the planned Chapter 40B development at 91 Beatrice Circle, as submitted by 91 Beatrice Circle LLC to Mass Housing on August 12. Graphic: 91 Beatrice Circle LLC.

Belmont is currently considering a Chapter 40B project. The description by 91 Beatrice Circle LLC submitted to MassHousing on August 12 states:

“91 Beatrice Circle is a 23,496 square foot site located along a frontage road of Route 2. The property is immediately adjacent to an MBTA bus station with access to Alewife Station. The project seeks to construct 12, four bedroom townhomes and detached single family units, with 25% of those homes being affordable to households earning 80% of the AMI.

The design incorporates high-quality, contemporary style architecture to create distinct, visually-interesting residences. The project’s massing and height is weighted along the Route 2 side of the property; along the southern side of the property, the project transitions to two-story, single family detached units to better integrate into the the single family land uses to the rear of the site. The homes have separate entrances and many include private outdoor spaces to provide a diverse, niche housing type relative to the many garden-style rental projects currently being built in the region. With 100% of the units having three or more bedrooms, the community creates new affordable housing options for families.

Belmont’s Status

As of 2015, Belmont had roughly 9,500 households; by 2018, Belmont was up to 9,719 households, according to the US Census. In June 2020, 675 housing units, or 6.7% of Belmont’s housing was affordable by Chapter 40B standards—but almost a quarter of Belmont households were eligible for affordable housing in 2018, according to the Belmont Housing Trust’s 2018 Belmont’s Housing Future: Housing Production Plan. Belmont residents are also spending a lot of money on housing: 44.3% of renters and 28.9% of current home owners were paying more than 30% of their income for housing as of 2018.

To attain safe-harbor status, Belmont needs either to add 50 units of affordable housing per year or to achieve 10% affordable housing. In 2017, Belmont had 10,117 households, and needed 1,012 units of affordable housing to meet the Chapter 40B standards—but only had 365 affordable units, (see “Belmont’s Housing Future,” November/December 2017). Belmont was 647 units short of reaching that 10% level, according to Belmont’s Housing Future: Housing Production Plan.

The Royal Belmont’s 60 affordable units—20% of the total—meant that 298 units were added to Belmont’s subsidized housing inventory, bringing the gap down to 349 units. The Bradford in Cushing Square only added 12 affordable units, less than 20% of the total 115 units, so only 12 units counted, bringing the number of units Belmont needs to be a safe harbor down to 337 units.

The 12-unit development proposed for 91 Beatrice Circle would add just three units to Belmont’s subsidized housing inventory—not enough to get Belmont to 10% affordable housing or to make Belmont a safe harbor from other Chapter 40B developments. Under Chapter 40B, though, Belmont may not have much choice over whether it gets built.

Meg Muckenhoupt is editor of the Belmont Citizens Forum Newsletter.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.