By Roger Wrubel

In 2009, Town Meeting adopted a Belmont Climate Action resolution committing to an 80% reduction in our town’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050. An inventory in 2015 found that Belmont had reduced its GHG emissions by 5% compared with 2007. The inventory showed that the most of Belmont’s emissions came from home heating and vehicles. Most of the reduction in emissions in the last nine years is attributable to a shift from using oil for home heating to natural gas, and a similar shift to natural gas from coal and oil to generate electricity for the New England grid.

In 2018, the Belmont Energy Committee issued Achieving Our Climate Action Plan: A Belmont Roadmap for Strategic Decarbonization. The roadmap showed that the rate of decline of emissions in Belmont was not sufficient to meet our 80% reduction goal by 2050. More aggressive action is needed. The roadmap calls for “strategic electrification” with electric heat pumps replacing 50% of oil heating systems by 2025 and 50% of gas heating systems by 2032, and for 50% of all new vehicles to be electric by 2030.

Electricity is the only form of energy we can produce without releasing greenhouse gases. No matter how efficient your gas furnace is and how much insulation you put in your house, you still need to burn natural gas to heat your house, which releases GHGs. But you can heat your house and heat your water efficiently with electric heat pumps without adding heat-trapping gases to the atmosphere by using solar, wind, and hydropower to produce electricity. If most of our electricity were produced from those three sources, electrifying houses and businesses would drastically reduce our carbon emissions and the rate of atmospheric warming.

For Belmont, the strategy involves moving to all-electric homes and transportation while transitioning the electric grid to 100% clean energy. Toward this end, Belmont Light’s strategic plan calls for moving to 100% renewable energy by 2022.

Electric Heat Pumps

Electric heat pumps are those square gray boxes that are becoming more common outside buildings. They are very efficient at moving heat from outdoors into buildings to heat them, even at typically low New England temperatures, and removing heat from inside a building for cooling. Heat pumps can also power water heaters. For more information on heat pumps and how they work, see bit.ly/MA_Heat_Pumps

Massachusetts has recently begun to consider its own roadmap to reach its own aggressive climate goals. In April 2020, the Executive Office of Environmental and Energy Affairs (EOEEA) issued a Letter of Determination establishing a GHG reduction target of at least 85% from 1990 levels by 2050 as the Commonwealth’s new legal emissions limit. State Senate and House bills addressing a pathway to reach the Commonwealth’s goals are now in conference committee: House bill H.4912, An Act to Create a 2050 Roadmap to a Clean and Thriving Commonwealth and Senate bill S.2477, An Act Setting Next Generation Climate Policy.

Why not natural gas?

Natural gas has been described as a bridge to a renewable clean energy future. This is because burning natural gas to generate electricity results in the release of 50% to 60% less carbon dioxide than oil and coal. Substituting natural gas for the other fossil fuels would allow us time, or the “bridge,” to develop new renewable, non-greenhouse gas-producing technologies to meet our climate goals. That goal should be to limit the increase in the average global temperature to 1.5°C, compared to preindustrial levels, as recommended by the International Panel on Climate Change. Have we reached the end of the bridge?

The Natural Gas Council ads promote natural gas as clean, reliable, and domestically produced with a clean, blue flame. Perhaps you have switched from an oil-burning furnace to an efficient gas furnace, paid for largely with gas utility subsidies. These campaigns have been successful. Total consumption of natural gas in the United States increased by 29% in the last 20 years while total consumption of energy has been essentially flat. Hundreds of coal-fired electric power plants have been replaced with natural gas generators.

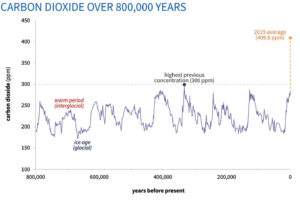

Burning natural gas still produces the greenhouse gas CO2, and lots of it, as carbon dioxide concentrations continue to rise. It is hard to imagine how either Belmont or Massachusetts can reach their climate goals in the next 20 to 30 years without immediately transitioning away from natural gas. Instead, the gas industry is trying to ensure that natural gas use will increase, as shown by their continued investment in gas infrastructure, including pipelines, gas compressors, and storage which will last decades. Do you think the industry is planning to abandon that infrastructure so we can eliminate emissions from fossil fuels by 2050?

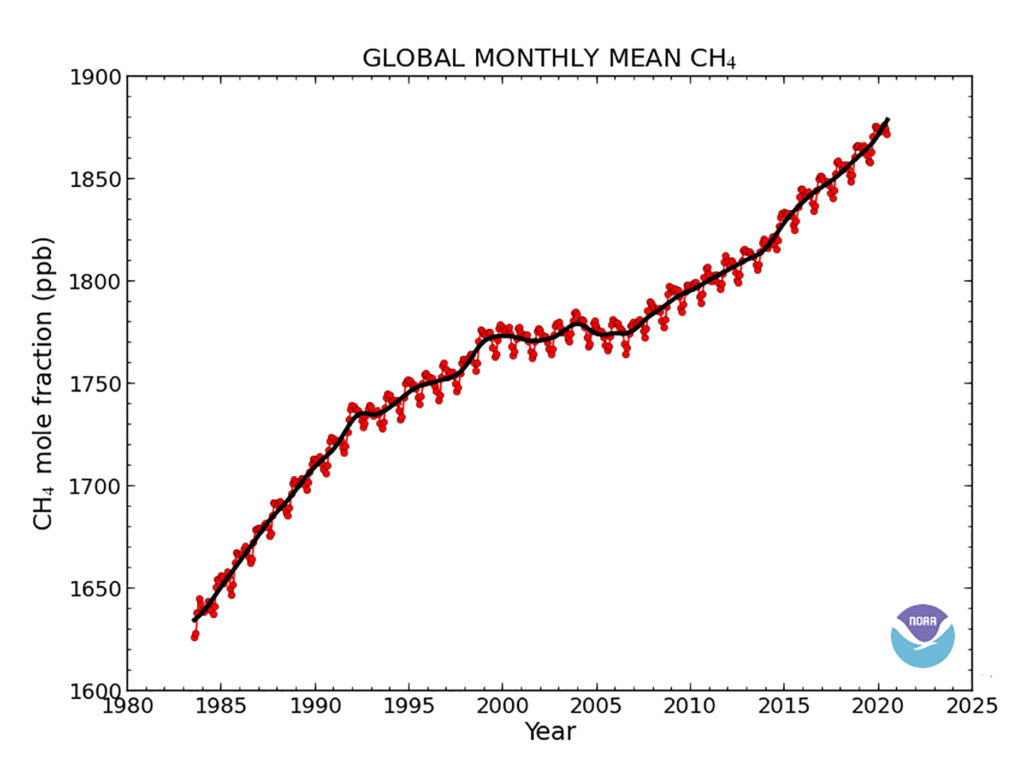

Besides carbon dioxide emissions, another troubling aspect of natural gas is that global methane concentrations in the atmosphere are also increasing. Natural gas is mostly methane, a carbon atom surrounded by four hydrogen atoms; natural gas that ends up in pipelines is about 95% to 98% methane. When methane is burned completely, the hydrogen-carbon bonds are broken, releasing energy as heat along with carbon dioxide and water.

Methane is released into the atmosphere by both natural and human activities. Methane is discharged from volcanoes and wetlands. Human-induced sources of methane include rice paddies, cows, landfills, and fossil-fuel production, transmission, and distribution. In most cities you can commonly smell methane leaking from underground pipes. Methane is actually odorless so mercaptan, which stinks, is added to natural gas so leaks can be detected.(See “80 Natural Gas Leaks in Belmont,” Belmont Citizens Forum Newsletter, May 2016.)

Methane is a much more powerful heat-trapping molecule than CO2, although its atmospheric concentration is much lower than that of CO2, and it cycles through the atmosphere much more rapidly than carbon dioxide. The half-life of methane in the atmosphere is about nine years, while CO2can hang around for centuries. Methane traps 86 times more heat than CO2 over a 20-year period. So methane must be reduced to keep global temperatures below critical levels by 2050. Reducing natural gas use within this short time frame is an essential part of the solution as the window of opportunity to act closes.

Since many houses in Belmont and our neighboring communities have fossil-fuel heating systems, converting to electric systems will take some time. Most homeowners will wait until they need to replace their fossil-fuel heating system unless there is an attractive incentive. But it makes sense to require electric heating, hot water, and cooking appliances in new construction to avoid installing GHG-emitting infrastructure that will last 15 or more years. This seems to me like a small first step, but there seems little appetite at the federal or state level to take on this issue. However, local legislative action has been gaining momentum.

In July 2019, Berkeley, California, became the first municipality in the United States to prohibit natural gas hookups in new construction. The ordinance was approved by the California Energy Commission in December 2019 and went into effect in January 2020. More than 30 other California local governments, including San Francisco, San Mateo, San Jose, Santa Monica, as well as Marin County, have adopted similar rules, as have municipalities in Oregon, Washington, Ohio, and New York. Industry sees the threat and has worked with several state legislatures, including Arizona, Tennessee, Louisiana and Oklahoma to prohibit restrictions on choice of utilities.

In November 2019, Brookline became the first municipality in Massachusetts to enact a restriction on fossil fuel infrastructure in new construction and major renovations. New laws in Massachusetts towns require approval by the state attorney general. In July 2020, Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey reluctantly rejected the ordinance, while expressing her office’s agreement with the objectives of the Brookline ordinance, citing preemption by existing state building codes, gas codes, and a law giving the Department of Public Utilities oversight of the sale and distribution of natural gas in Massachusetts.

What has been happening in Belmont

Since it was created by the Select Board in 2010, Belmont’s Energy Committee (EC) has spearheaded efforts with Belmont Light to reduce the town’s carbon footprint in a variety of ways, including inventorying GHG emissions and running clean energy campaigns: a residential energy efficiency campaign, Belmont Drives Electric, Belmont Heat Smart (encouraging electric heat pumps), and Belmont Goes Solar. In 2011, Belmont adopted the Massachusetts Stretch Building Code which required a higher level of energy efficiency in new construction and major renovations.

Marty Bitner, EC co-chair, states that the EC wants to engage with all town committees and town officials to make climate considerations front and center in the town’s decisions. To this end, the EC has had a seat at the table in planning the new Belmont Middle and High School, now under construction, which will be zero-net energy and have no natural gas service. A general definition of a zero net energy building is that the amount of energy provided by on-site renewable energy sources is at least equal to the amount of energy used by the building (see www.energy.gov/eere/buildings/zero-energy-buildings). The EC has also worked closely with the Library Building Committee to shape that project, which is still in the planning phase. Bitner believes the library will also be zero-net energy without natural gas service.

EC members also have worked with the Planning Board and a developer to shape a condo/apartment project planned for the McLean subdistrict above Pleasant Street. While this development is likely to have natural gas infrastructure, the developer has agreed to have electric heating and cooling and some water heating with electric heat pumps as well as offering electric induction-cooking ranges.

Bitner said that the EC had readied an Emission-Free zoning by-law similar to the Brookline bylaw to present at Town Meeting. When the attorney general rejected the Brookline bylaw, Belmont’s bylaw had to be shelved. Bitner said the EC is now studying legal alternatives: having the legislature pass an emission-free electrification bylaw for the entire state prohibiting fossil-fuel use for heating in houses and other buildings, or allowing each municipality to have the right to pass its own emission-free bylaw.

Bitner says there are four possible paths forward for emission-free electrification in Belmont.

A nonbinding resolution. Belmont Town Meeting could pass a nonbinding resolution demanding the state enact legislation requiring electric heat and cooling in new construction, so that the state could comply with its own Global Warming Solutions Act adopted in 2008 as well as the Letter of Determination recently issued by EOEEA. The town could coordinate delivering parallel resolutions issued by other municipalities to enhance its impact.

A home rule petition. Belmont Town Meeting could pass a home rule petition asking the state legislature for the power to prohibit fossil fuels in new construction, so the town could comply with its Climate Action Plan.

Zoning. Communities can use their own zoning authority to encourage, but not require, building electrification. Incentives might include building height or density bonuses.

Net Zero Stretch Code. Belmont Town Meeting can instruct the Energy Committee and the Select Board to join other municipalities across the state to insist that the Board of Building Regulation and Standards (BBRS), which writes the state building code, add a Net Zero Stretch Code to the basic building code. The original Stretch Code has not been updated since it was created in 2008 and is now out of date. Communities choosing to adopt the Net Zero Stretch Code would require modern standards of energy efficiency for new construction and renovations.

Switching to natural gas from coal and oil resulted in a reduction in CO2 emissions from electrical generation in the United States. However, the release of methane during the production, transmission, and distribution of natural gas may have cancelled out most of the benefits of the switch.

Compared with the timeline at which climate change is occurring, the timeline and extent of human reaction is too little and too slow, as evidence mounts that climate change is accelerating. The severity of the danger calls for acting quickly and boldly to reduce carbon emissions to avoid a long period of climate change and increasingly intense natural disasters.

What you can do to help

Follow the deliberations of Belmont’s Energy Committee and support their efforts to bring climate considerations front and center in all town decisions.

Contact the Select Board and our state House and Senate representatives urging state action to support electrification in all new construction and major renovations, or a home rule petition that would allow Belmont to take action if the town desired.

Contact the Select Board and our state House and Senate representatives and ask them to lobby the state for passage of a net zero stretch code.

Roger Wrubel is a Town Meeting Member for Precinct 5 and recently retired after 20 years as director of the Habitat Education Center and Wildlife Sanctuary.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.