By Meg Muckenhoupt

Since aggressively upzoning the Alewife area a decade ago, Cambridge has permitted hundreds of thousands of square feet of new development in the Quadrangle neighborhood adjacent to Belmont, and bordered by Fresh Pond Parkway, Fitchburg line railroad tracks—and Concord Avenue. Now, even more development could solve some long-standing transportation issues, or it could make getting out of Belmont or traveling around the entire Fresh Pond area even more difficult.

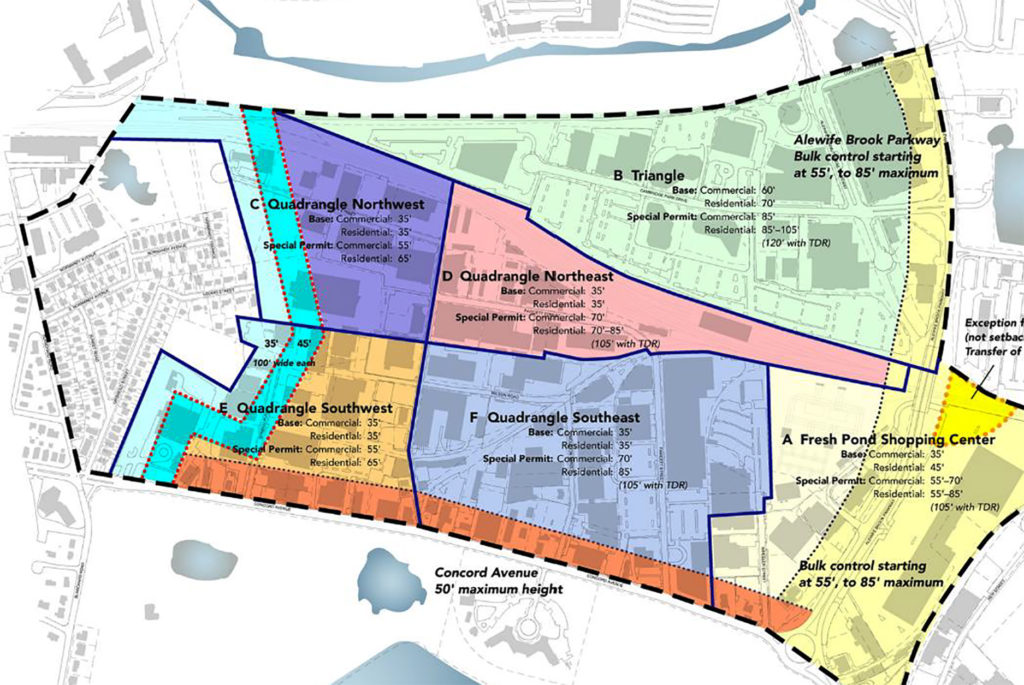

A map of the Quadrangle area from the 2019 Alewife District Plan.

Why build in the Quadrangle now?

Unlike the rest of Cambridge, the Quadrangle has a history of sparse development. Originally one of the lowest-lying areas of the Mystic River watershed, it’s smack in the middle of what colonial-era maps labeled “The Great Swamp.” For much of the 20th century, the area was home to primarily industrial sites and “urban-edge” businesses which provide essential services that would disrupt residential neighborhoods: warehouses, truck-loading areas, supply depots, and parking lots. There were few sidewalks, fewer trees, and hardly any housing.

Part of the reason for little development, apart from marshy beginnings, is the lack of connections between the Quadrangle and the rest of Cambridge. The Quadrangle is bounded on the north by train tracks. All its roads empty onto Concord Avenue. The lack of connections across the tracks and Alewife Brook Parkway turns what should be brief trips to grocery stores, restaurants, and the Alewife T stop into lengthy expeditions, whether you choose to walk, bike, or drive. (Current development of 55 Wheeler Street is supposed to provide pedestrian and bike connections between Fawcett and Wheeler Streets, which will shorten the trip to Alewife Brook Parkway.)

The 2005 Concord Alewife Plan Report divided the Quadrangle into three zones—residential, mixed use, and mixed use/light industrial. The city of Cambridge sought to increase the amount of housing and resident-friendly businesses by splitting the area into four overlay districts: Quadrangle Northwest, Northeast, Southwest, and Southeast.

In 2006, Cambridge rezoned the entire Quadrangle, along with the Triangle (the area between the railroad tracks and Alewife Station) and the “Shopping Center” (the area along Alewife Brook Parkway) creating a total of six Alewife Overlay Districts (AOD).

The four Quadrangle overlay districts (Northwest, Northeast, Southwest, and Southeast) differ principally in two factors:

Floor area ratio (FAR): This is the ratio of built space to the area of the building lot. For the Quadrangle Northwest and Northeast districts, the maximum FAR is 1.5 for all uses. In the Southwest and Southeast districts, the maximum FAR is 1.5 for nonresidential uses, and 2.0 for residential uses—encouraging denser development of housing.

The Northwest and Northeast overlay districts also restrict building heights near the Cambridge Highlands neighborhood, Russell Park, and Blair Pond. Any portion of a building within 100 feet of residential or open space zoning is restricted to 35 feet; within 200 feet of that zoning, the building is limited to 45 feet.

The Quadrangle’s Alewife Overlay Districts as illustrated in the City of Cambridge’s 2018 Alewife Zoning Recommendations. Figures indicate the maximum heights permitted.

Runaway success, runaway traffic

The 2005 Concord Alewife Plan Report predicted a surge in new development in the Quadrangle area in Appendix C, “Anticipated and Development: Predicted & Proposed Zoning.” Unfortunately, that report didn’t anticipate just how popular the area was going to be.

In the past 10 years, developers have built 588 housing units and more than 683,067 square feet of housing, commercial, and retail space in the Quadrangle area. Buildings currently under construction, permitted, or proposed would bring total housing units to 1,816 and increase total construction to 2,623,250 square feet.

Square feet of development in Quadrangle

| Predicted SF | Built as of 2020 | Permitted/under construction | Proposed | Total built/permitted/proposed |

| 1,175,493 | 683,067 | 783,329 | 1,201,854 | 2,623,250 |

Housing units in Quadrangle

| Predicted | Built as of 2020 | Permitted/under construction | Proposed | Total built/permitted/proposed |

Sources: 2005 Concord Alewife Plan Report, Appendix C, “Anticipated Development Under Existing and Proposed Zoning,” Cambridge Community Development Locator Map, Doug Brown/ Fresh Pond Residents Alliance.

Those numbers matter because Cambridge has been slow to acknowledge just how fast the Quadrangle has been developing, or the traffic impacts of Quadrangle development. The 2019 Alewife District Plan states, “Based on an analysis of building trends in Alewife, roughly 60% of the total projected development in the Quadrangle may be realized by 2030,” but as of 2020, developers have already built 20% more square footage than the total predicted build-out. A May 2018 presentation by the Alewife District Plan Committee predicted an additional 725 housing units at 60% build-out of the Quadrangle by 2030, but 1,267 new housing units already have either been built, are under construction, or been permitted for the area.

That’s a lot of people traveling to work each day. According to the 2019 Alewife District Plan, 53% of Cambridge residents living in and around Alewife commute by car. All the new car trips from the Quadrangle must end up on Concord Avenue.

In 2016, the city’s Envision Cambridge Alewife Working Group published an analysis of the Quadrangle’s intersections at Concord Avenue, to see how many cars could fit through the intersections before traffic came to a standstill. Intersections at Fresh Pond with 1,500 or fewer vehicles per hour can allow motorists to get through intersections in two light cycles or fewer: with more than 1,500 vehicles per hour, traffic begins to “deteriorate exponentially.”

According to that 2016 analysis, the intersection at Fawcett Street and Concord Avenue would exceed those numbers by 2030 under the proposed Envision Cambridge Plan. That exponential traffic deterioration may happen much sooner.

A 2017 traffic analysis of just one Quadrangle development site—55 Wheeler Street, where Abt Associates is building 525 units of housing and 448 parking spaces—was predicted to produce “added delay of more than 20 seconds” at both Fawcett and Wheeler Streets during rush hours, dragging down both intersections to an “F” level of service, with wait times of more than 120 seconds per car at both intersections along Concord Avenue. That’s just for one development, where planners optimistically estimated only an additional 58 to 62 car trips per hour during morning and evening rush hours in their 2017 application narrative, due to Wheeler Streets proximity to the T. (The “proximity” in the 2017 design depends heavily on a “potential bike/pedestrian connection” to the as-yet-unplanned bridge; that feature remains on the 2020 design update.)

Another 144 units are already under construction, and an additional 549 are already planned. What will the state’s standard be for worse-than-”F” intersections? 240 seconds waiting? 480? Gridlock?

Certainly, there could be alternatives to driving around Alewife. The 55 Wheeler Street development is supposed to include a pedestrian pathway to connect Wheeler Street to the shops and restaurants along Alewife Brook Parkway. The many visions for greenways wending through the Quadrangle would make biking and walking attractive and convenient.

Detail of illustration of potential green space connections from Envision Cambridge’s 2019 Alewife District Plan. Note the swooping green space ending at Wheeler Street, where the Alewife District Plan envisions a pedestrian/bicycle bridge.

Unfortunately, these greenways don’t exist yet. And some of them may never exist if the current owners of 15.9 acres of the Quadrangle have their way.

Cabot, Cabot & Forbes (CC&F) purchased 11.9 acres of the Quadrangle along Mooney Street in 2018, and an additional four acres at 67 Smith Place in October 2020. Now, CC&F has asked Cambridge’s Planning Board to rezone 26 acres of the Quadrangle, comprising the Northwest quadrant plus a good chunk of the Southwest, to allow 85-foot-high commercial buildings. In exchange for the rezoning for 85-foot buildings and a .25 ratio increase in the FAR, CC&F says it will build a bridge across the railroad tracks.

In most communities, rezoning a parcel primarily owned by a single developer would be “spot zoning,” which is illegal in Massachusetts. It’s outlawed because the zoning existed for a reason. A developer’s short-term interests in maximizing profits often don’t mesh with community interests in good traffic flow, access to transportation, reduced flooding, or green space.

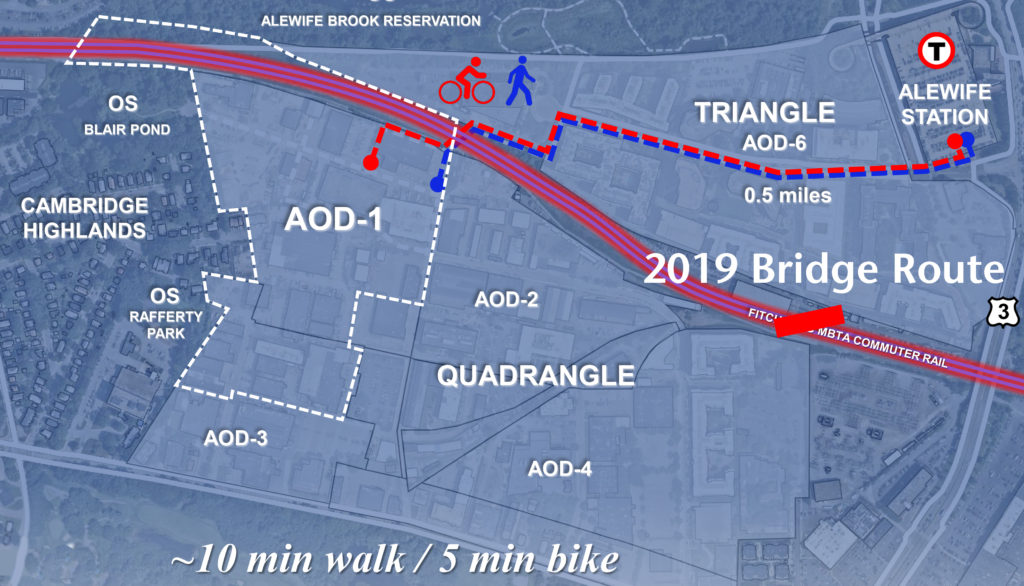

Top: bridge plan by CC&F as presented to Cambridge’s Planning Board on December 8, 2020, with the addition of the bridge route envisioned in Cambridge’s 2019 Alewife District Plan (bottom).

Cambridge’s contract zoning habit

The city of Cambridge justifies spot-zoning to suit developers by calling it “contract zoning.” In contract zoning, developers get to build much more densely in exchange for providing some kind of public amenity. In a letter to Cambridge Day, Cambridge resident and one-time City Council candidate Ilan Levy described how the MIT Investment Management Company (MITIMCo), the investment arm of MIT, bought 10 acres of land at a Kendall Square site for $750 million. In exchange for promising to replace a Department of Transportation building for $500 million, the Cambridge Planning Board extended the maximum building height from 85 feet to 300 to 500 feet for MITIMCo’s five planned towers. $500 million is a small price to pay for increasing the square footage of your development by up to 600%—and local residents and commuters will be paying the price for decades in clogged streets, Red Line delays, long shadows, and winter wind tunnels. Taken together, the dense buildings planned for Kendall Square are predicted to consume 100 megawatts of electricity, doubling Cambridge’s city-wide electrical consumption. They will also require a new electrical substation in a densely populated area.

In the case of CC&F, the public amenity in question is the bridge. Cambridge has been wishing for a bridge at least since the city published its Alewife Revitalization Plan in 1979, but never dedicated money to actually building it. At a December 8, 2020, meeting of the Cambridge Planning Board, CC&F presented its plan for building that bridge—and rezoning the area for 85-foot-high commercial buildings, not 55 feet.

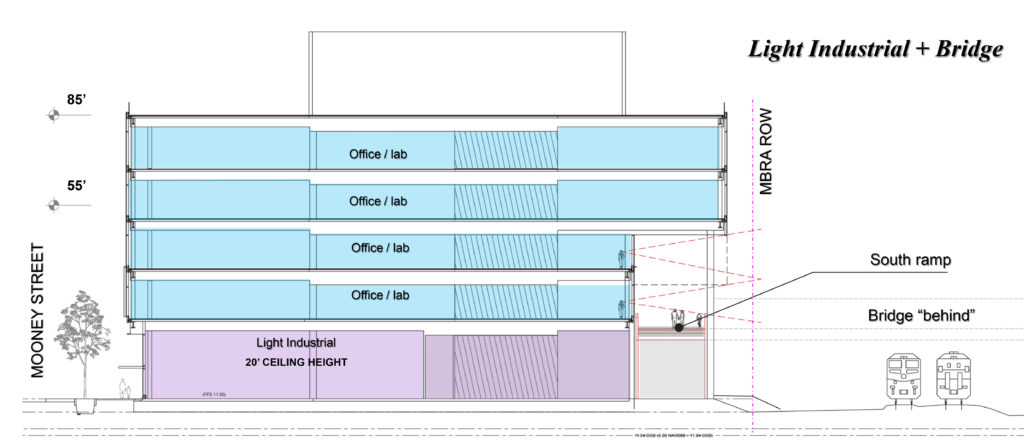

Depiction of a 55’ vs. 85’ building with an attached bridge from CC&F’s December 8 presentation to the Cambridge Planning Board.

CC&F’s plan is great for CC&F. It will double the amount of office and lab space it can build, adding two more floors above the currently allowed 20-foot “light industrial” first story and two floors of commercial space. And it does call for builders to submit transportation plans with measures to “offset or mitigate the development proposal’s impacts on transportation systems.” But with 26 acres of 85-foot office buildings, is it even possible to mitigate the traffic exiting onto Concord Avenue?

Also, the bridge CC&F is offering isn’t what Cambridge had in mind. CC&F’s proposed bridge would be located at the end of Smith Place, and is a light-use bridge for bicyclists and pedestrians only. That location doesn’t make the bridge terribly convenient for the rest of the Quadrangle’s residents and workers. The 2019 Alewife District Plan recommended a bridge near Wheeler Street, and stated that the city should “evaluate a second bicycle/pedestrian bridge across Alewife Brook between Discovery Park and Cambridgepark Drive in the long term.”

Cambridge might be better served by a bridge that could also carry motor vehicles. In February 2018, the Cambridge City Council voted to “have City Manager Louis DePasquale explore the feasibility of conducting a transit study and action plan to explore the feasibility of a shuttle bus bridge from the Quadrangle area along Concord Avenue across the railroad tracks to the Triangle area on Cambridgepark Drive,” according to Wicked Local Cambridge. The council also asked DePasquale to look into adding a commuter rail stop in the area. Unfortunately, as of this writing, this project was still “awaiting report.”

The Smith Place bridge would still be more than a half-mile from any entrances to the Alewife MBTA Station—a distance that can be challenging during winter sleet, and impossible for many people with disabilities or small children in tow. Without shuttle-bus access to the bridge, anyone who cannot move up to a mile under their own power will end up driving, or taking a Lyft, Uber, or bus on Concord Avenue—where traffic will already be at a standstill. CC&F offered even more troubling changes to their rezoning scheme in a December 4 revision to the rezoning petition, adding language to allow developers to contribute to a fund for the bridge instead of building it or designing their properties to accommodate it, with no mention of timing of these payments and no requirement for shuttle access. The bridge could simply be “delayed” for another 40 years.

As of this writing, the Cambridge City Council has not adopted the 2019 Alewife District Plan and its vision of a “cohesive mixed-use district” that will “enhance the public realm,” and “encourage sustainable modes of transportation.” Unfortunately, that allows developers to come to the planning board with zoning changes that are incompatible with that plan, like the CC&F proposal. CC&F has not even submitted an application for a building permit. Presumably they are waiting until the zoning changes.

Given Cambridge’s pro-growth approach to Kendall Square, it’s hard to believe that the city will discourage maximum build-out at the Quadrangle. The consequences may be overwhelming for Belmont. “If you snapped your fingers and the [CC&F upzoning] project were done, finished today, you would not be able to drive on Concord Avenue,” said Doug Brown, an officer of the Fresh Pond Residents’ Alliance.

Meg Muckenhoupt is executive editor of the Belmont Citizens Forum Newsletter.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.