By Jane Sherwin

Until the mid-20th century, agriculture was a significant part of Belmont life and economy. Three hundred years ago, it would have been unusual to find a family in this area with no engagement at all in growing things. Even a shoemaker would most likely have a few chickens, or a milk cow, or a small garden for vegetables.

The settlements on the land that is now Belmont go back nearly four hundred years. In 1630, Sir Richard Saltonstall led a group of families inland from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, to the area we now call Watertown, to start their own agricultural community. Long before the Europeans arrived, of course, Native American peoples had cultivated the land, growing corn and other crops.

In the 17th century, farming in New England had a strong communal aspect. Common lands were essential for grazing animals and for the hay that would feed them through the winter. Farming also was largely sustainable. Farmers grew enough crops and raised enough livestock to feed their families and pay for essentials they could not produce.

As the years passed, and Belmont’s population grew, farms were divided to meet the needs of succeeding generations, and common lands were divided and sold to individual farmers. As the economy changed, the farms changed too. Farmers began to concentrate on crops to sell to the growing city of Boston, and they discovered the powers of greenhouse cultivation. In 1859, for its seal, Belmont chose Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruits and gardens. She stands surrounded by an abundance of produce, with the Town’s rolling hills in the background.

For the first hundred years of its life as a town, Belmont remained a vital farming community. Belmont’s farms characterized our beginning in 1859, as Frances Baldwin describes so well in her book, The Story of Belmont:

“Though Belmont had become a town in name, in fact it was scarcely a village. Rather it was a wide-spread collection of profitable fruit farms and market gardens, whose owners spent long sun-up to sun-down days cultivating the rich black earth and reaping the harvests thereof. Between Mr. Marsh’s hill-top farm at the northern end of town and . . . the southern Payson Park area, there stretched as beautiful an expanse of orchards, gardens and shimmering greenhouses, as could be found anywhere in New England.”

By the time of Belmont’s 1859 incorporation, there were several types of agriculture in town.

- Farms settled as early as 1630, many diminished in size but still active

- Farms of 10 to 25 acres, some farmed by descendants and some by newcomers

- Orchards large and small

- Dairies and stock farms, established for breeding of cattle or race horses, so-called “fast” horses.

- There were also the estates purchased by wealthy families from the city like the Underwoods, who considered farming to be an important part of their role in life. They built greenhouses and cultivated orchards and gardens for learning and pleasure.

Belmont became famous for the quality and size of our produce. Baldwin says that Belmont was known for fruits and vegetables as the city of Paris was known for its ladies’ fashions. Belmont farmers were written up in agricultural magazines and newspapers.

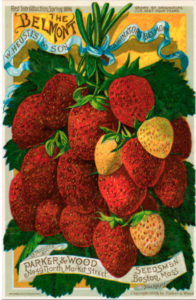

Belmont farmers won prizes for their strawberries and held an annual Strawberry Festival that drew thousands. Belmont farmers were written up in agricultural magazines and newspapers for their strawberries, including the Colonel Cheney and Belmont varieties, and also for pears and apples such as the Clairgeau, the Roxbury Russet, the Red Astrachan, and Clapp’s Favorite. The Belmont gardenia remains a favorite of gardeners today all over the world.

Farmers and landowners with an interest in livestock imported cattle and pigs from Europe, sometimes introducing breeds to the United States. There were the dairies, from a cow or two all the way to a herd, selling milk in glass bottles which you can see at the Belmont Historical Society, located in the Claflin Room of the Belmont Public Library.

Our farmers were active in the Massachusetts State Farm Bureau and the Boston Market Gardeners Association. They served on committees of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society and were honored in its lectures and publications. They formed the Belmont Farmers’ Club, and had long evening discussions about the best ways to manage orchards and prevent plant diseases.

Immigrants from Italy, Ireland, and Poland rode the trolleys from the North End to labor in Belmont’s larger market gardens. Many immigrants worked from 7 AM to 5 PM, pulling celery from the ground, hauling it to the wash house, and loading the crates for delivery to Boston. Later they rented or purchased property for their own farms.

Belmont’s market gardeners farmed very differently from the husbandry of colonial times, and yet even they used techniques that might be called “sustainable”. Until the 1940s, farmers used few pesticides and chemical fertilizers. In fact, the record of pre-World War II agriculture is almost entirely a literature of what we now call “alternative” agriculture, according to the Cornell Agriculture Library’s web site, which is well worth a read.

By the late 19th century, Belmont was full of greenhouses, farms and market gardens, designed and operated to produce fruits and vegetables and flowers destined for Quincy Market. The demand for this produce was so great that farmers could afford to build elegant homes and to send their children to college. Many of these farms lasted 100 years and more, in the same family.

Most remarkable of all, we have the Belmont Acres Farm (formerly the Sergi Farm), owned and farmed by a single family and their descendants since the 17th century. Today, Mike Chase and his family farm this land in cooperation with the current owners, the Ogilby family. Belmont Acres was once the Hill/Richardson Farm, and is the last remaining part of the original 1633 land grant from King Charles I of England to Abraham Hill. The original grant ran from the remaining acres in Belmont all the way to Charlestown and the harbor. The Ogilbys have placed the land in an agricultural trust.

Belmont Abandons Agriculture

When refrigeration became available to market gardeners in the South, California and other faraway places, Belmont growers faced serious competition. With the Great Depression of 1929 and the manufacturing demands of World War II, people who had grown up on farms were encouraged by their parents to find another line of work. At some point, the tax valuation of land for residence became greater than the value of land for farming.

By 1950, land as real estate had become Belmont’s chief asset. The real estate agent became the farmer’s friend, saying, “I can take that land off your hands for you.” The relatively sudden disappearance of agriculture is a loss that we all may feel, even those of us who came to Belmont decades after the removal of the last commercial greenhouses. When land becomes a commodity, our perceptions of it and our obligations toward it become very different. We lose the emotional tie, the “love of the land” that is so often part of farming.

It is not as though we suddenly stopped growing things after World War II, of course. There are private vegetable gardens all over town. The community gardens at Rock Meadow are a great place to visit any time during the growing season. If you walk along the west side of Pequossette Park, you’ll see backyards facing the soccer field filled with densely cultivated gardens: grapevines, tomatoes, green beans, cabbages, squash.

And the ending? By the late nineteenth century railroads and streetcars had made living in Belmont an attractive choice for people who worked in the city of Boston but wanted to live out in the country.

The same population that provided a market for our strawberries and celery was the population that wanted a good place to live within easy reach of the city. The Belmont Herald stated in 1954, “Progress will and must come with the constant demand for additional land for development in such a desirable residential community as Belmont.”

Once our farms had gone (with the exception of the Sergi farm), who were we? The “Town of Homes” phrase suggests the difficulty of defining a new identity. The earliest reference to this phrase was in advertising by the McGinniss coal yard in Waverley Square in the 1920s and 30s: “We heat Belmont, the Town of Homes.” But doesn’t it go without saying that, if you are a town, you have homes? Are we a Town of Homes because we have nothing else? Are we to be defined by an advertisement? Perhaps our agricultural history can help widen our understanding of who we are.

There are many signs of our farms. The next time you notice an old pear tree or an apple tree with a sturdy trunk, you may well be looking at a part of Belmont’s orchards. Everywhere you go in Belmont you can see farm buildings and houses— homes that were built for farm families to live in. Some of them are as old as the first settlers, some of them were built as late as the 20th century.

Belmont will always have our history as a town that appeared suddenly, just before the Civil War, a town that used to be parts of other towns. But the farms and market gardens and greenhouses offer a continuity between the early settlements, Belmont’s incorporation as a town, and the present. The one remaining farm, open spaces, and farm buildings are tangible evidence of the centrality of farming to our story. The more we know and understand this part of our history, the greater will be our connection to the life of our community.

Jane Sherwin is a Belmont resident with a longstanding interest in Belmont’s agricultural history. This article is based on a series of her talks.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.