By Jeffrey North

Tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima), typically called ailanthus, is a rapacious deciduous tree native to China. It was first introduced into the United States when it was imported as an ornamental plant to Philadelphia in 1784 and later to New York in 1820. On the West Coast, immigrants brought the plant from Asia and planted it in California in the 1850s.

The tree was initially valued as a fast-growing ornamental shade tree that was tolerant of poor soils and a broad range of site conditions. It tolerates vehicle exhaust and other air pollution quite nicely. It was widely planted all along the Northeast Corridor, especially from Washington, DC, to New York City, for a hundred years, until the early 1900s, when it gradually lost some of its popularity. Its “weedy” nature, prolific root sprouting, and foul odor caused a drop in the plant pop charts.

Today tree of heaven has spread to 46 states and much of Canada to become an all-too-common invasive plant in urban, agricultural, and forest edge areas. We are not alone. The tree also has been introduced in Argentina, Australia, and Africa. Ailanthus spreads from human settlements, with roads, railroads, and areas of disturbed soil providing the migration routes.

But that does not mean that you have to tolerate it.

So What’s The Problem?

Ailanthus altissima crowds out native species, damages pavement and building foundations, and fails to supply food or habitat to native creatures. Its roots can damage sewer lines. It grows almost anywhere, in cracks in turnpikes and bridge abutments, deforested parcels, parking lots, along rivers and streams, along woodland edges, roadsides, railways, in forest openings, and urban wilds. Tree of heaven will quickly colonize disturbed areas and take advantage of forests weakened by insects or damaged by wind and storm events or fire.

Tree of heaven serves as host to the brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys, in California and, especially worrying in the Northeast, the spotted lanternfly, Lycorma delicatula. As if all that were not enough, tree of heaven also produces allelopathic chemicals in its leaves, roots, and bark that poison other species’ root systems, slowing or preventing their growth. Ailanthus is truly a plant for the zombie apocalypse.

Identification

The best way to identify the tree is by its leaves. Ailanthus resembles native sumac and hickory species, but it is easily distinguished by the glandular, notched base on each leaflet. Just remember the phrase, “sumac is serrated, but tree of heaven is smooth.” It can grow to 80 feet tall and 3 feet or more in diameter. Its bark is smooth and brownish-green when young, eventually turning light brown to gray, then slightly furrowed, resembling the skin of a cantaloupe.

Detail of Ailanthus leaves showing small bumps called “glandular teeth” near the base of the leaf. Source:Dave Jackson/ Penn State Extension

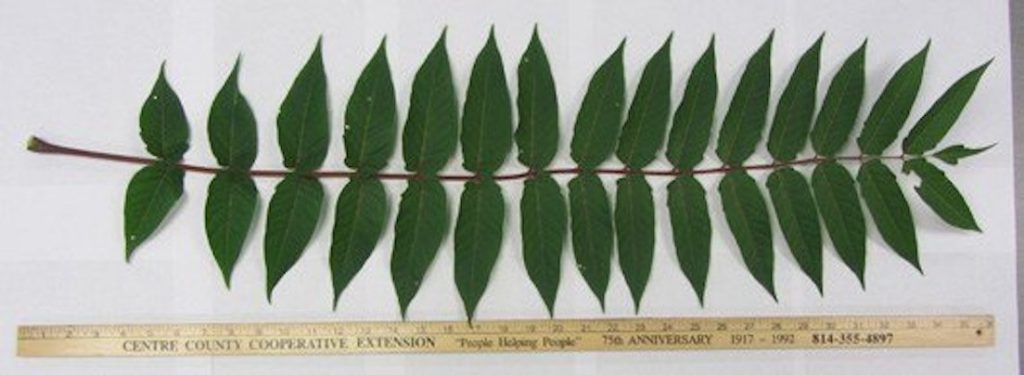

Tree of heaven leaves have a central stem to which leaflets are attached on each side. One leaf can range in length from one to four feet with anywhere from 10 to 40 leaflets. The leaflets are lance-shaped with smooth margins. At the base of each leaflet is one to two protruding bumps called glandular teeth. When crushed, the leaves and all plant parts give off a strong, offensive odor.

Typical Ailanthus stem Note the opposite leaflets attached to a central stem. Source:Dave Jackson/ Penn State Extension

Look-a-likes

This species is easily confused with some of our native trees that have compound leaves and numerous leaflets, such as staghorn sumac, black walnut, and hickory. The leaflet edges of these native trees all have teeth, called serrations, while those of tree of heaven are smooth. The foul odor produced by the crushed foliage and broken twigs is also unique to tree of heaven.

Reproduction and Conquest

An ailanthus tree is either male or female, and typically grows in dense colonies, or “clones.” All trees in a single clone are of the same sex. Female trees can produce more than 300,000 seeds annually, and sprouts as young as two years old are capable of producing seeds. The seeds are dispersed by the wind.

Established trees spread by continually sending up root suckers as far as 50 feet from the parent tree. A cut or injured tree of heaven may send up dozens of stump and root sprouts. This characteristic has important implications for the control of this invasive tree species.

Human Health Concerns

Tree of heaven can adversely affect human health. The tree is a great producer of pollen that can cause allergic reactions for some. Skin irritation or dermatitis can occur from contact with leaves, branches, seeds, and bark, and in rare cases myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle) can result from exposure to sap through broken skin, blisters, or cuts.

Anyone faced with extensive exposure to the tree should wear gloves and protective clothing. Avoid contact with the sap. Seek medical attention if you experience fever or chills, chest pain (especially if it radiates down both arms), and shortness of breath.

Treatment

Young seedlings with stems two inches or less in diameter can be dug up and removed if the soil is moist and the entire root system can be removed. Like other non-native invaders, the plant can regrow from just a root fragment. Due to its extensive root system and its resprouting ability, tree of heaven is difficult to control. Seedlings can be easily confused with root suckers, which are nearly impossible to pull by hand. According to experts, treatment timing and multiyear follow-up are critical to success.

University extension programs offer good guidance on the treatment of this and other invasive plant species. The College of Agricultural Science extension program at Penn State University suggests that when attempting to remove or neutralize tree of heaven, applying an herbicide is necessary. This is best done by a licensed applicator. Herbicide must be carried down into the root system to stop further sprouting. When symptoms of herbicide exposure develop (approximately 30 days), then cut down the tree.

Systemic herbicides should be applied in mid- to late summer when the tree is moving carbohydrates to the roots. Herbicide applications made outside this late growing season window will only injure above-ground growth. Following treatment, repeated site monitoring for signs of regrowth is critical to prevent reinfestation.

Herbicides applied to foliage, bark, or cuts on the stem can be effective at controlling tree of heaven. Applying herbicide to stumps, however, does not prevent root suckering and should not be utilized. For most treatments, use herbicides containing glyphosate or triclopyr because they have little or no soil activity and pose little risk to nontarget plants.

Well-established tree of heaven stands are only eliminated through repeated efforts and monitoring. Initial treatments often only reduce the root systems, making follow-up measures necessary. Persistence is the key to success.

Any removal efforts within 100 feet of wetland resource areas will require approval from the Belmont Conservation Commission.

In Support of Biodiversity in Belmont

The Invasive Working Group (IWG) of Belmont’s Land Management Committee is currently developing a plan to remove or neutralize the trees of heaven on Belmont’s Lone Tree Hill conservation land. Contact bcfprogramdirector@gmail.com or lonetreehillbelmont@gmail.com for more information or to be connected with an IWG volunteer.

Alternatives

The following native plants can serve as a good replacement for Ailanthus according to the Concord,MA, Division of Natural Resources:

- Hickories (Carya spp.)

- Green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica)

- Butternut (Juglans cinerea)

- Smooth sumac (Rhus glabra)

- Staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina)

Jeffrey North is the managing editor of the Belmont Citizens Forum and chair of the Invasives Working Group of the Land Management Committee for Lone Tree Hill.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.