By Kristin Anderson and David White

We are at an important point in the history of the Alewife Brook. The Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA) and the cities of Cambridge and Somerville are preparing a new long-term sewage control plan for the Alewife Brook/Upper Mystic River Watershed. Climate change, with its wetter rainy season, more intense storms, and sea level rise, is expected to result in more hazardous Alewife Brook sewage pollution and more flooding in the area. During some storms, the Alewife Brook floods into the houses, parks, and yards of area residents in environmental justice communities. Because of the health risk of exposure to the sewage-contaminated flood water, it is imperative that investments be made to improve water quality in the Alewife Brook and the Little River.

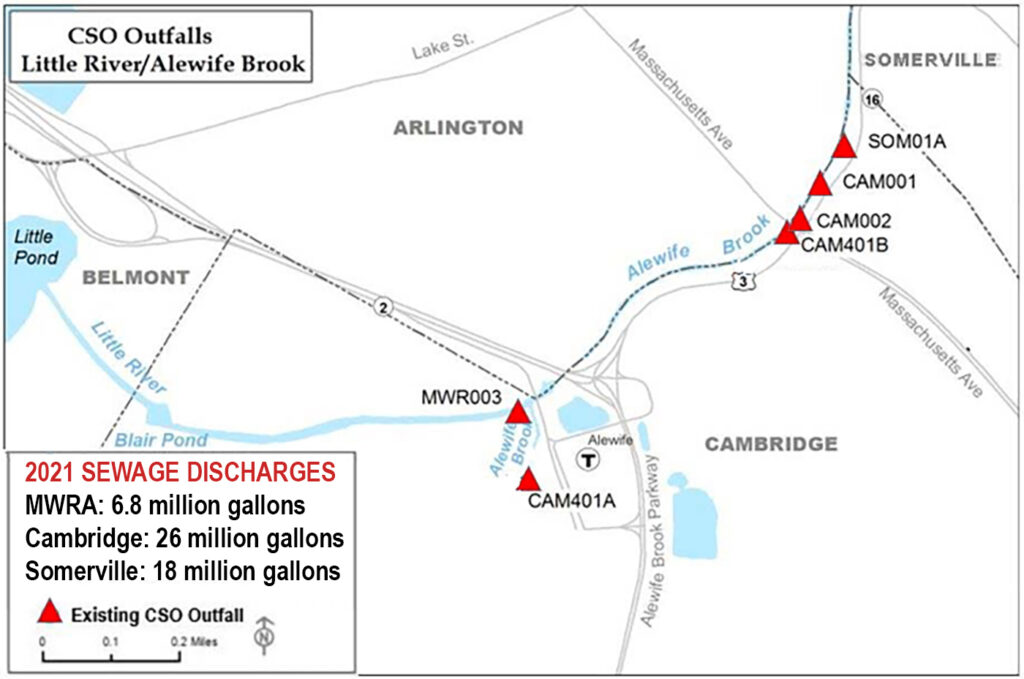

There are still six combined sewer outfalls (CSO) on Alewife Brook and the Little River.

Let’s look back to the years between 1994 and 2015 when the MWRA created and implemented its first CSO control plan. The main goal of the first CSO control plan was to reduce CSO discharges to rivers and streams that run to Boston Harbor as part of the Boston Harbor cleanup. As part of the MWRA’s larger plan, the goal for Alewife Brook was to reduce annual average CSO discharges of 27 million gallons of untreated sewage pollution down to 7 million gallons.

The centerpiece of the Alewife CSO projects was the Alewife Stormwater Wetland. This public park was the largest and most beautiful example of green stormwater infrastructure in the Northeast at the time of its construction. The constructed wetlands improve water quality and slow the flow of stormwater into the Little River, which flows into the Alewife Brook and on through the Mystic River to Boston Harbor. The detention of stormwater at the wetlands also reduces area flooding.

The Alewife stormwater wetland was completed in 2015. It was the capstone of more than $110 million spent on projects spanning more than a decade to reduce Alewife sewage pollution. The projects of the first Long Term Control Plan resulted in the closing of six combined sewer outfalls, sewer separation in two catchment areas covering 273 acres in Cambridge, nineteen small green stormwater infrastructure projects, and the large constructed stormwater wetland. When these projects were completed in 2015, common belief was that the Alewife sewage pollution problem was solved.

It was quite alarming when, in 2021, more than 50 million gallons of untreated sewage pollution were dumped into the Alewife Brook. Twenty-two million gallons came from Cambridge. Eighteen million gallons came from Somerville. And MWRA dumped seven million gallons of untreated sewage pollution from Belmont and Cambridge into the Little River immediately upstream of the Alewife Brook. The MWRA’s CSO, MWR003, is connected to the Cambridge Rindge Avenue Siphon and Belmont’s Relief Sewer. Belmont doesn’t even have a combined sewer system, yet untreated sewage from Belmont is being discharged into the Little River by MWRA.

Why is untreated, raw sewage still flowing into a narrow brook in a densely populated, flood-prone area that includes environmental justice populations?

To understand why the Alewife Brook is still suffering from such serious pollution in 2023, we must acknowledge that the state, through the MWRA, viewed the Alewife as a small part of a more significant problem that had to be addressed when the Massachusetts was ordered to clean up Boston Harbor in a series of court orders in the 1980’s. The MWRA identified where they could achieve the biggest bang for their buck. Sewer projects were prioritized by looking at how much of an improvement in water quality could be achieved for Boston Harbor, and at what price.

Because cleaning up the Alewife would not have a significant impact on the water quality of Boston Harbor, Alewife Brook received only half measures. Six of the CSO outlets into the Alewife Brook were closed, but six still remain open and are in use. In fact, Alewife Brook’s poor water quality grade was weaponized by MWRA. The MWRA argued against greater investment in improving public health conditions in the Alewife because the brook is so severely polluted that eliminating CSOs would not yield a significant improvement in the water quality.

The major causes of poor water quality in Alewife Brook are combined sewer discharges, stormwater runoff, stormwater outfalls (which may also contain sewage), and contaminated sediments. The sediment contamination comes from sewage, stormwater, and discharges from local industry. Further upstream, pollution from Belmont flows from Winn Brook to Little River to Alewife Brook.

These factors all contribute to poor water quality, but their relative importance is not clearly understood. The MWRA’s 2014 water quality report shows that the CSO and stormwater control work performed from 1989 to 1991 and from 2000 to 2014 has significantly reduced E. coli counts in all conditions, especially in heavy rain as shown in Figure 4-9 of that report. But on average, wet weather level counts are about 10 times those of drier conditions. Dry weather counts are down some but are still above the violation threshold. It does not appear that stormwater is the only problem, rather that it is more complicated, and improvements are needed in many areas.

EPA provides guidance

During major floods, CSO-contaminated flood water enters the homes, yards, and parks of the area’s environmental justice (EJ) populations. Twenty years ago, when the first sewage control plan projects began, EPA and the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) did not have a mandate to protect EJ populations. Today, the EPA and MassDEP take seriously their responsibility to help reduce harmful environmental impacts on EJ populations.

In 2022, the EPA wrote to MWRA, asking the agency to work with the Department of Conservation and Recreation to dredge the brook. Dredging would improve water quality by removing contaminants and reducing bacterial counts in the water on dry weather days. Currently, water quality remains poor even on dry weather days when a lack of CSO and stormwater discharges should mean better water quality.

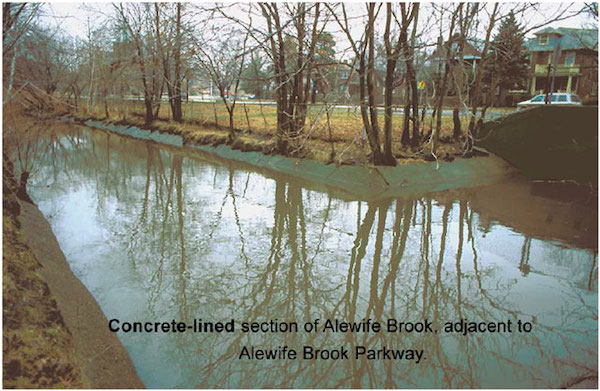

Because the Alewife is such a small and slow-moving river, nothing more than a narrow concrete channel in some places, it has accumulated several feet of CSO-contaminated sediment. During most conditions, the sediment lies beneath a foot of water. During last summer’s drought, however, there were only a couple of inches of water above the sediment in places, and the stench was unbearable. High bacterial counts likely exist because the sediment contributes to the poor water quality.

Green stormwater infrastructure

In 2022, EPA also wrote to the cities of Cambridge and Somerville, asking them to invest in green stormwater infrastructure to clean and reduce the amount of stormwater entering the combined sewer systems and the brook. Upstream remedies like rain gardens, tree trenches, and permeable pavement, and downstream projects like the constructed wetlands must be employed to clean the water and reduce stormwater flows and flooding. Removal of the concrete channel and restoration of the brook could reduce flooding by creating additional capacity for stormwater.

The cities of Cambridge and Somerville must employ green stormwater infrastructure as part of the new sewage control plan. However, there should also be a more comprehensive regional effort. For the Alewife Brook, Belmont and Arlington must join efforts to plan new green stormwater infrastructure solutions to improve stormwater quality and reduce flooding.

Sewer separation

EPA has also asked the cities to separate their sewers. To close the Alewife’s six remaining active CSOs, the old combined sewer pipes in Cambridge and Somerville must be separated. This means the cities must excavate roads to access the sewer lines and separate their Victorian-era combined sewer pipes. As part of the new Alewife sewage control plan, both cities need to commit to an ambitious sewer separation program.

Regional sewer system upgrades

The communities in the Alewife sub-watershed cannot solve the problem without the help of MWRA because the combined sewer pipes and outfalls are tied into its aging and undersized regional sewer system, which is failing to meet current conditions. According to MWRA consultant Don Walker, there is not enough capacity in the MWRA’s system to manage flows to the Deer Island wastewater treatment plant during some storms. That is when sewage pollution is discharged into Alewife Brook.

The EPA has asked MWRA to improve its sewer infrastructure by employing gray infrastructure solutions such as underground CSO detention tanks, upgrades to its Alewife sewer lines, and increased downstream capacity. Perhaps MWRA could also construct an Alewife CSO treatment facility behind the Alewife T parking garage.

New state sewage control legislation

Where there is political will, money plus time can solve the problem. But here, political will is naturally splintered because the Alewife Brook marks the boundary between four separate municipalities: Arlington, Belmont, Cambridge, and Somerville. And the city of Medford is just yards away from where the Alewife meets the Mystic River. Historically, polluters clutched their purse strings, closed their eyes, held their noses, and sent their pollution downstream, where it became someone else’s nightmare. This is why the Alewife needs help from the state.

The Commonwealth can greatly improve water quality by passing legislation to bring all combined sewer overflows in the MWRA’s sewer system area to a 25-year level of control, meaning untreated sewage pollution would be discharged on average only once every 25 years. This is the standard that is currently applied to other CSOs in the Boston area. That would be a big step towards addressing the problem while the cities continue to separate their antique combined sewer lines.

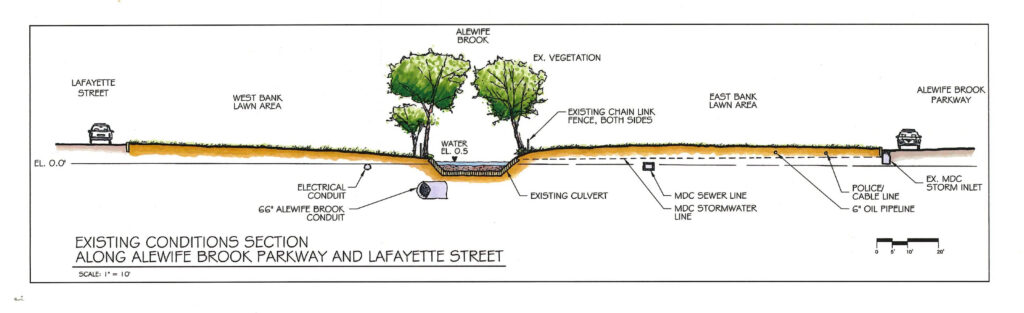

Alewife Master Plan update

While it is dated, the 2003 Alewife Master Plan contains large and small green infrastructure projects that could be constructed today. An Alewife Master Plan update could look to the future by focusing on climate adaptation and hazard mitigation projects that would protect residents and community assets in the Alewife basin’s densely settled low-lying neighborhoods in Belmont, Cambridge, Arlington, and Somerville. An Alewife Master Plan update could provide shovel-ready projects to be paid for with the ample federal and state funding soon to be disbursed from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Inflation Reduction Act.

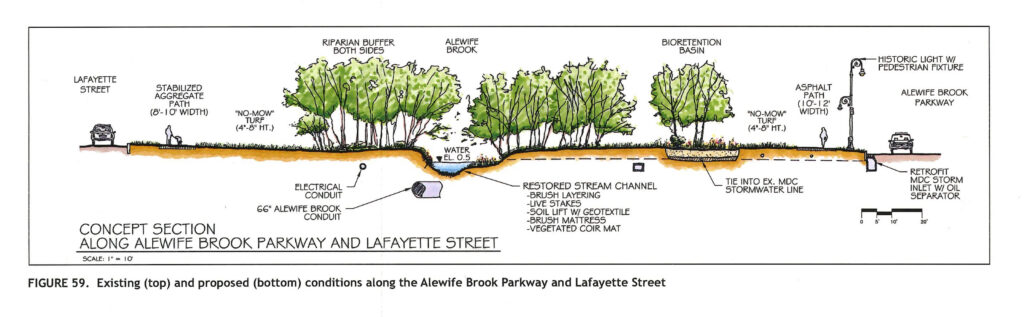

Alewife Brook dechannelization and restoration sketches from the Department of Conservation and Recreation’s 2003 Alewife Master Plan.

The Alewife brook needs a hydrological study of water quality, flows, storm capacity, sedimentation, and contamination within the sediment.

Over the last few decades, there have been multiple studies of the sediments showing that it contains toxins, including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and heavy metals. Removing the toxins in the sediment through dredging would protect the health of the thousands of residents living within the Alewife’s 100-year floodplain, including the area’s substantial environmental justice populations. A new hydrological and dredging study will allow us to take advantage of state and federal funding opportunities around climate adaptation, flood mitigation, water quality, hazard mitigation, and environmental health. Furthermore, such a study might reveal that the Alewife Brook should be considered for a Superfund site designation.

A lot has changed in 20 years; the effects of global warming and our understanding of the possible solutions. It is time for a new assessment and new actions that look toward the future. Cambridge and Somerville and MWRA are legally obliged to make investments to reduce their sewage pollution, but that will not be enough. For the Alewife to receive the care it deserves, Belmont and Arlington must implement green stormwater infrastructure to clean their stormwater and reduce flooding. Finally, we must see state support for assessment, leading to federal support for action to remove hazardous sediment and restore the Alewife Brook to a healthy state.

Thanks to members of the Save the Alewife Brook Steering Committee who contributed comments and content to this article: Gwen Speeth, David Stoff, and Gene Benson.

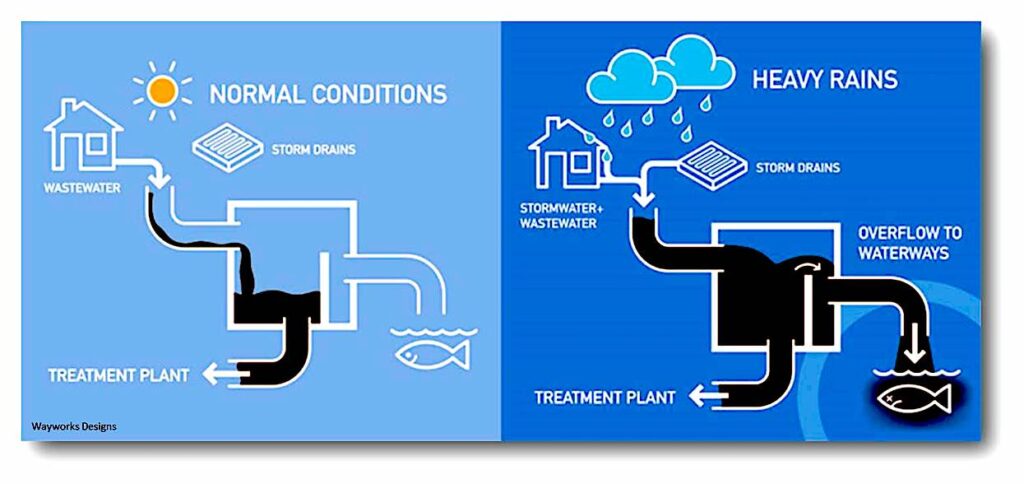

A combined sewer system. During dry weather (and small storms), all flows are handled by the publicly owned treatment works (POTW). During large storms, the relief structure allows some of the combined stormwater and sewage to be discharged untreated to an adjacent water body via a Combined Sewer Outfall (CSO). From U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) “Report to Congress: Impacts and Control of CSOs and SSOs.”

Kristin Anderson is an Arlington Town Meeting member whose home was occupied by the untreated sewage flood waters of the Alewife Brook during more than one 100-year flood event within two years. David White is an Arlington Conservation Commissioner. The authors can be contacted at arlington@savethealewifebrook.org or savethealewifebrook.org.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.