By Anne-Marie Lambert

There’s a lot of complexity but not much bureaucracy involved when beavers take action to manage stormwater. Beavers don’t follow many rules and regulations to slow down a brook’s flow to a prescribed amount or filter pollutants like phosphates or nitrates. They don’t submit maintenance plans for what they will do differently when large rainstorms or new pollutants arrive. Beavers don’t wait for permit approvals or make decisions based on a checklist of laws and regulations.

Beavers have evolved to build their homes across brooks to create whole new ecosystems that support many species that have evolved to flourish in a wetland or meadow environment. They are an integral part of a dynamic and evolving ecosystem full of other species also responding to evolving conditions. More humans are also recognizing how effective nature-based solutions can be.

As far as I know, no beavers exist in Belmont. Instead, we have written a Storm Water Management Plan (SWMP) and a Municipal Vulnerability Program (MVP) Action Plan to state our intention to deal with pollution and flooding. These plans aim to abide by rules and regulations that have evolved from the 1972 Clean Water Act to address pollution and reduce flooding and other risks from climate change.

It took more than 50 years, but in 2024, we humans are finally starting to learn how helpful it can be to recreate the kind of swamps beavers used to build and maintain before we hunted them close to extinction. We call these lessons on ways to slow down and infiltrate stormwater into the soil Best Management Practices (BMPs). We’re not doing it as efficiently as beavers would, but at least we are moving in that direction.

Curbing Pollution

One remarkable thing about beavers is how they create an environment where pollution-eating bacteria can thrive. Beaver dams don’t wait for debris to collect in a cement catch basin or on an asphalt road. They pack mud and cellulose-rich material in the base of their dams, attracting bacteria that absorb nitrogen and phosphorus compounds from the water stream.

In 1972, our elected officials voted to give the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) authority to set standards for how much pollution would be allowed to flow from the drainpipes of a town like Belmont—known as a “separate storm sewer system (S4)”—into the nation’s waters (e.g., Boston Harbor).

The EPA set up a permit system called the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) to do this. Under this system, Belmont has to apply for a permit to discharge stormwater from its drain pipes into the Mystic River and Charles River. This permit is known as the NPDES General Permit for Stormwater Discharges from Small Municipal S4s in Massachusetts or the MS4 General Permit.

Of course, rain—known as “stormwater” according to the regulations—falls on Belmont and finds its way into soil and drainpipes, with or without regulations. Whether or not Belmont meets the permit requirements, gravity (with occasional help from electric pumps) ensures that the rainwater in Belmont’s drain pipes flows to the end of each pipe—known as an “outfall”—into rivers, streams, and ponds.

The EPA can’t block the flow of rainwater coming out of Belmont just because it is polluted. What the EPA can do is impose a fine or threaten to impose a fine, as it did in 2017.

From 2017 to 2022, Belmont was under an EPA Administrative Order on Consent that required Belmont to try harder to find and fix the sources of pollution or risk having to pay large fines. In those five years, through our Illicit Discharge Detection and Elimination (IDDE) program, Belmont removed an estimated 6,839 gallons per day of sewage that had previously been discharging into our waterways. It cost $2,336,000.

After sampling stormwater outfalls repeatedly in wet and dry weather, the town identified cracked pipes and illicit discharges. Engineers did targeted dyed-water testing and took CCTV videos inside the drains. The town’s 2020–2022 Sewer System Rehab I/I Removal Project included lining 8-to-10-inch vitrified clay pipe sewers, replacing a full-length 8-inch sewer, lining service laterals, replacing service laterals, doing point repairs, and rehabilitating manholes.

In addition, as part of the town’s Pavement Management Plan, we did point repairs to gravity sewers and storm drains and replaced sewer and storm drain service laterals and connections. We installed new sewer and storm drain manholes. In July 2021, the town began a Private Sector Sump Pump Removal & Sewer System Rehabilitation Construction Project to perform ongoing point repairs, service lateral replacements, cured-in-place main line lining, and rehabilitate or remove contamination sources (see Table 4 of the Final Compliance Memorandum.)

Meanwhile, overlapping with that order on consent, in 2019, Belmont was “permitted” to discharge stormwater into rivers and ponds in accordance with its MS4 General Permit. Besides the Illicit Discharge Detection and Elimination activities, this permit requires developing a plan that addresses public education and outreach, construction and post-construction site stormwater runoff control, pollution prevention, and “good housekeeping” in municipal operations. In this context, “good housekeeping” includes street sweeping and regular cleaning of our catch basins. Are we finally becoming as fastidious as beavers?

The town kept looking, and by December 2022, it identified and eliminated illicit connections on Van Ness Road and at a manhole at Oliver Road/Staunton Road. These areas flow into Beaver Brook and Winn’s Brook, respectively.

This is a lot of progress, but there is more to do. By mid-February 2024, a full set of documents related to its SWMP was posted on the town website, including annual MS4 reports through June 2023 and the daunting 92-page IDDE report. The annual MS4 report for the year ending June 2023 identified several future priorities, such as an investigation of the neighborhood surrounding Shaw Road, a possible illicit connection on Hartley Road, and ongoing investigations to identify the source of E.coli pollution at Outfall 27 near Stony Brook Road (a small catchment basin draining into a wetland that drains into Beaver Brook), and at Outfall 10 (the Winn’s Brook outlet into Little Pond, one of the two largest catchment basins in Belmont). We added a storm drain layer to the town’s GIS map to provide a detailed view of the location of each outfall and drain pipe (see table on p. 53 of the IDDE report).

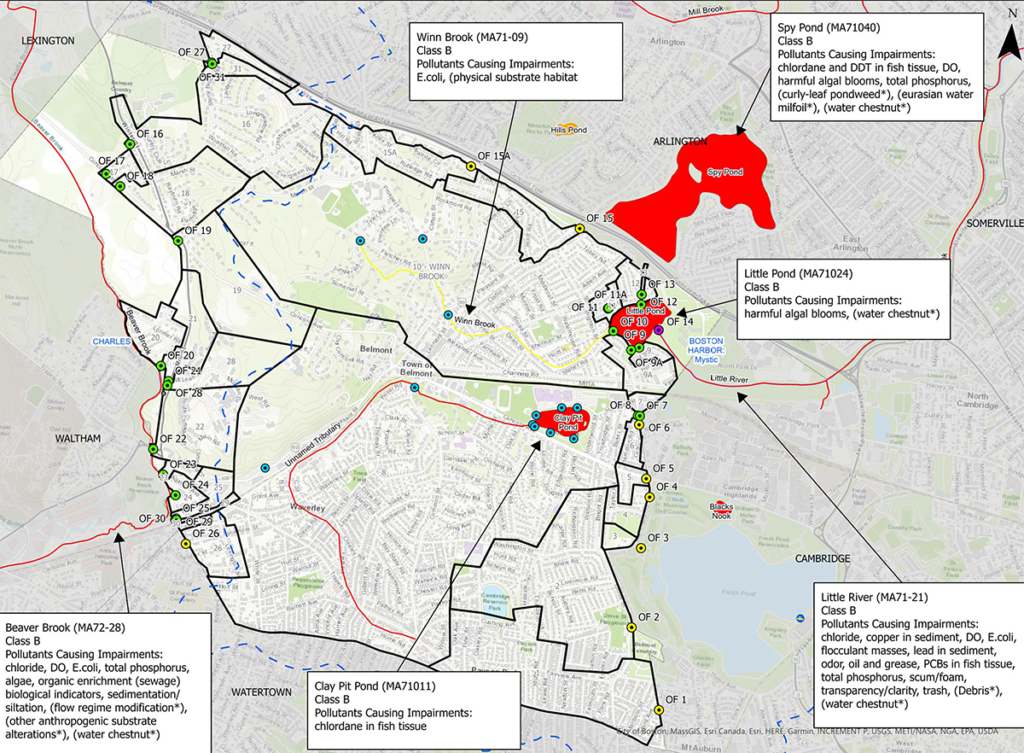

Map showing the primary pollutants affecting significant water bodies in Belmont: Winn’s Brook, Little Pond, Little River, Clay Pit Pond/Wellington Brook, Beaver Brook, and Spy Pond in Arlington. Figure from Town of Belmont Illicit Discharge Detection and Elimination (IDDE) Program, Revised 2023.

We paid special attention to pollutants for which a Total Maximum Daily Load has been calculated for the Charles and Mystic rivers, as required by the MS4 permit. The town now has a 20-year plan to reduce phosphorus runoff to the Charles River, including applying BMPs for street design and parking lots that would serve to slow down and infiltrate stormwater runoff into the soil—almost as effectively as beavers do.

Stormwater management designs for the new Belmont library and the Viglirolo skating rink could provide impressive examples for others. The Conservation Commission has already encouraged BMPs like the permeable pavement and rain garden they required to help treat runoff from the Belmont Manor parking lot and building extension. Five town-owned parking lots have been identified as candidates for BMPs such as retention basins and rain gardens.

It would be great if some privately owned parking lots followed these practices, such as the even larger parking lots that are associated with churches, synagogues, and private schools. BMP practices are inching Belmont towards cleaning up our waterways at a time when storms are becoming more frequent and more intense, and the more participation, the better.

Map of Beaver Brook from DCR Brochure.

Flooding at Beaver Brook

While beavers are known in some circles as nuisance animals that cause flooding, they can help improve what would otherwise be a much worse situation downstream. They carefully consider seasonal weather conditions, diverting tributaries and holding back water that would otherwise overwhelm downstream landscapes. Their work helps replenish water tables rather than letting rain go as fast as possible into the ocean. Without the active beaver communities of centuries past, water tables all over America are reaching some of their lowest recorded levels.

The Beaver Brook Culvert

One of the top flooding vulnerabilities in Belmont is the undersized Beaver Brook culvert under Trapelo Road. Metal plates have been positioned over the road for some time to stabilize it in case the culvert collapses. After a few days of heavy rain, I visited Beaver Brook Reservation North on March 31, and I can see why.

The flooding on the northern side was impressive as the torrent of water from the cascade upstream wended its way through an expanding warren of tributaries in about 10 acres of low marshland and woods, then along the Trapelo Road embankment and to the culvert and beyond. The erosion at the pothole by the Route 60 sign near the plates was also remarkable. It was easy to imagine beavers making their home here, as they must have over 100 years ago, slowing down and releasing all this water at a pace that would not overwhelm a bottleneck like a culvert.

For about 20 years, humans have spilled a lot of ink discussing this culvert but not fixing it. One idea was to repair it as part of the Trapelo Road/Belmont Street Restoration Project, begun in 2005. The culvert repair was scrapped when Belmont and Waltham couldn’t agree on which town should pay for what. In October 2014, the city of Waltham published a request for proposals to repair the culvert or at least stabilize it.

In 2018, Belmont received an earmark from the state for $100,000 for a larger project. The remaining funds ($791,975) were to come from the sewer enterprise fund. In 2020, Belmont completed its Municipal Vulnerability Preparedness Assessment Report, listing this culvert as one of its top-five projects. Though that application was not successful, in July 2022, the Massachusetts House and Senate appropriated $2 million in state funds to address the restoration of the culvert replacement.

Later in 2022, the Waltham and Belmont Conservation Commissions reviewed the project and stipulated that the project schedule should avoid the spring river herring spawning season. In October of 2022, Waltham issued a request for bids. Finally, on March 7, 2023, Waltham granted a contract to E.T. & L. Corporation, stipulating in the purchase order that Waltham and Belmont will each pay 50% of the project cost. A project plan will now break ground in the summer of 2024 after high water has subsided and any river herring has spawned.

As towns navigate rules and regulations, budgets, and culverts, more and more storms continue to arrive, increasing both the risk of Trapelo Road becoming impassable and downstream flooding in Waltham. The cascade upstream of the culvert formerly powered the Plympton Mill and other mills in the 1600s and 1700s. It is impressive after spring rains. This year, the man-made Duck Pond was so full that three “extra” waterfalls joined the cascade down the steep slope on the south side. More water was squeezing its way between the stones that comprise the dam at an alarming volume.

Suppose we are going to address the effects of climate change. In that case, we have to learn to function as an integral part of a dynamic and evolving ecosystem full of other species—and other towns—that are responding to evolving conditions.

Current programs for permitting and funding are slower than the systems they are trying to regulate, and current priorities appear blind to systemic risks that will profoundly affect Belmont citizens and infrastructure. The BMPs planned for the new library represent a hopeful recognition of the effectiveness of nature-based systems, which hold back water before it gets channeled into a concrete culvert. They are a great start, as are watershed-based regulations that reach across municipal boundaries to take care of our rivers.

Maybe in another 50 years, we’ll have a permitting system that allows us to reintroduce beavers to manage stormwater—and to teach kids important lessons about ways to recognize and respond to changes within a dynamic ecosystem.

Anne-Marie Lambert cofounded the Belmont Stormwater Working Group, a collaboration between Belmont Citizens Forum and Sustainable Belmont. She is a Precinct 2 Town Meeting member and former Belmont Citizens Forum director.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.