By Elissa Ely

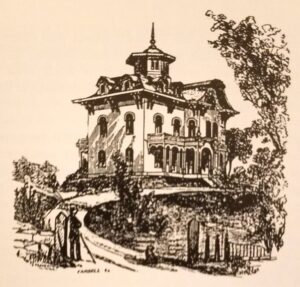

“What is that house?” Wendy Murphy thought the first time she saw the mansion at 661 Pleasant Street: elevated, magisterial, remote, uninhabited, yet somehow alive. “Is it haunted?”

The William Flagg Homer House is neither inhabited nor haunted, though it is alive with architecture and art. As president of the Belmont Woman’s Club, Wendy became one of its protectors. Her decade-long tenure exceeds term limits, though not for lack of a successor search. “I’m like a general contractor,” she says ruefully, “and the problem with being productive is that no one wants to be that busy.”

The Homer House deserves its own book. So does the Belmont Woman’s Club. So does Wendy Murphy, who has just written her own: Oh No He Didn’t! Brilliant Women and the Men Who Took Credit for Their Work. Three books are impossible in 1,100 words. I will do what I can.

In 1920, when women won the right to vote, the Belmont Woman’s Club came into existence. From inception, it was a gathering place for all classes, not—contrary to stereotype—somewhere to host the upraised pinkies of the wealthy. “These were women who were very smart but had no place to be smart,” says Wendy. “Once the 19th amendment was adopted, it was like a gushing, swirling groundswell nationwide.” The groundswell permitted women a metaphorical and literal liberation from their houses. Members joined and stayed; at least two current Belmont Woman’s Club members are more than 100 years old.

Their charitable mission hasn’t changed: education, philanthropy, community service. “There’s a barrier between what we know we’re doing and what the public thinks,” Wendy says. “We work hard to get the word out.” They fundraise for scholarships for graduating Belmont High School students, host free lectures on topics like civil rights, hold tours, co-sponsor family activities on the rolling lawn with the library and recreation departments, and even offered their rooms when the library needed to relocate books before renovation.

What has changed since 1920 is the admission criteria: early members were usually Irish and married (Wendy is the first president not to use her husband’s last name). All genders and ethnicities, as well as non-Belmontians, are welcome now.

The member with the highest personal stake in the Belmont Woman’s Club might be Homer House itself, purchased by the club in 1927 before women had a legal right to buy homes. Boston merchant William Homer, uncle of artist Winslow, constructed it in 1853 on land originally owned by Roger Wellington of elementary school fame. The Homers built four elegant floors topped by a cupola for their summer home. It was an awfully long commute from their winter home in Boston.

Winslow Homer loved the place, and reproductions of his paintings hang on all floors. Some are pastoral and rich with youth. Some are more daring, like a waist-coated croquet player peeping at the dainty ankle of his partner.

Originally, there was no electricity or plumbing, though hand-painted tiles from Holland lined the copper bathing tubs, the kitchen ceiling was hammered metal, wooden doors were carved magically into curves, and the ice box was so large it needed its own separate room. One staircase floated, and a bell pull on the first floor ran to the third-floor servant quarters, where servants were assumed perpetually available. More important than supernatural rumors was the possibility that a narrow secret space—almost unendurably tight—between kitchen and dining room served as a stop on the Underground Railroad.

Inch by inch, room by room, window by window, this place on a hill has been maintained and upgraded by the Woman’s Club. “We use a defensive approach,” says Wendy, “We ask: What’s the worst problem we have to take on right now?” With boxes of tools and bottles of cleaners tucked into corners, she takes on a good deal of maintenance herself. “My skill set has improved with YouTube,” she explains.

Larger projects—like replacing stained glass or regrading an unascendable driveway—have required benefaction. About a decade ago, the club donated the land on which the Homer House sits to the Belmont Land Trust. “We wanted to make it unusable to a developer,” Wendy explains. “We have no money. It’s all coming to us through the Land Trust.”

This suburban elegance is a long distance from Wendy’s day job. Working for the Middlesex County DA as a young lawyer (having already been a competitive baton twirler and a New England Patriots cheerleader—stories that must wait for the next book), she was assigned to child abuse and sex crime cases. Their victims were disproportionately girls and women, and—she felt—treated crudely by the very legal system meant to protect them. Eventually, she left for private practice. “Eighty percent is pro bono. It’s like a nonprofit law firm on purpose because I wanted to change things.”

She became an adjunct professor of Sexual Violence and Law Reform at New England Law School. She also founded the Women and Children’s Advocacy Project, litigating to advance their constitutional rights (once suing former U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos for efforts to weaken Title IX). “We never conceive of the suffering of women as a public injury,” she argues. “I don‘t pretend to think I can fix the system, but I can irritate it. I’m scholarly but also in the trenches.”

Now she represents an entire class, as well as abused individuals within it. “I enjoy my freedom to be a rabble-rousing activist lawyer and call myself an impact litigator,” she says. “I want my students to fix the law, not obey the law.”

The world is full of ugliness, which most of us prefer not to notice unless we must. Wendy sees it, hears it, and attends professionally to its devastation. The mission exacts a personal price—you can’t unknow evil. But Homer House and the Belmont Woman’s Club are part of her therapeutic antidote. They bring a bit of beauty back.

In her own Belmont home, there is no floating staircase or hammered ceilings. She hangs tile, builds walls, and recently installed a French drain in the yard. “Retirement doesn’t appeal to me,” she insists, though should you care to become president of the Woman’s Club, please do contact her. “Less stress and fishing do.”

Elissa Ely is a community psychiatrist.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.