By Vincent Stanton, Jr.

Thought you could escape coronavirus news in the pages of the BCF Newsletter? You are safe, but there is a catch. If you can tolerate more grim news, consider taking a trip back to the last global pandemic, the so-called “Spanish Influenza” of 1918. The story of how Belmont responded is replete with both striking similarities to the 2020 coronavirus response and sharp differences.

A weekly record of the influenza pandemic as it swept through Belmont in the fall of 1918 can be found in the pages of the Belmont Patriot. However, before diving into the influenza news, here is a bit of context about our main source and the times.

The Belmont Patriot was an unusual newspaper. First, as the masthead declared just below the title, it was “Published Under the Auspices of the Belmont Public Safety Committee,” a group of citizen volunteers organized to encourage and coordinate a range of town-wide activities in support of the United States war effort. Many sons of Belmont were fighting in Europe or training to deploy there; indeed, most of the front-page news was about their exploits. Every city and town in Massachusetts had a public safety committee which operated under the umbrella of the Massachusetts Committee on Public Safety.

Second, the Patriot did not carry bylines. Some committee reports were signed, as were letters to the editor, but page one stories never had an author. Third, the Patriot lasted just one year. With the surrender of Germany on November 11, 1918, marking the end of hostilities, the Patriot no longer had a reason to exist, and published its last issue six weeks later on December 28, 1918.

Given the mission of the newspaper, and the broader social context of a war mobilization effort that had taken over the US economy and inflicted some degree of privation on virtually every citizen, the influenza epidemic was generally not headline news, even as Belmont citizens died on the home front. In Washington, DC, the influenza pandemic was regarded as a serious hindrance to the US military in the fall of 1918, and was underplayed by the Wilson administration as it focused on defeating Germany.

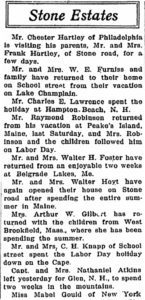

The Patriot was a four-page newspaper, published on Saturday, with regular features on each page. On page 3, running under the heading “Local Items,” was an account of social events in Belmont neighborhoods: the comings and goings of children and house guests, vacation destinations, who attended what parties, and the like (see, for example, the excerpt below from the “Local Items” on September 7). News that the recurrent influenza epidemic had reached Belmont in the fall of 1918 first appeared not on the front page, but in a single sentence in the page 3 “Local Items“ column of September 14, where it was noted that “ . . . Spanish Influenza . . . is quite prevalent at this time.”

The following week, flu news dominated the “Local Items” on page 3, with reports of flu cases in Waverley, Harvard Lawn, and Clark Hill, including the news that “Dr. Wm C. Hanson is a very busy man these days. Increasing cases of Spanish Influenza has [sic] kept him working night and day and last Sunday he was ordered to the sailors’ hospital at Corey Hill to treat several cases of the sickness there.” There was still nothing on the front page of the Patriot, however, and Belmont held a primary election on September 24.

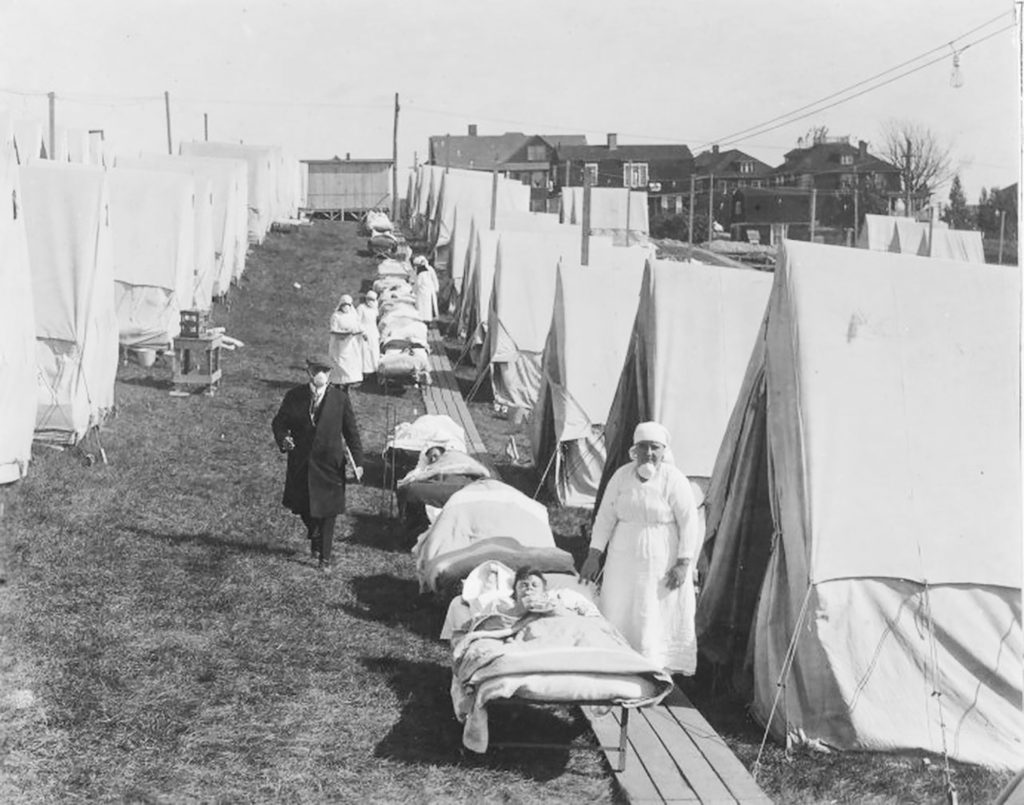

To put this low-key coverage in context, consider that the “hospital at Corey Hill” referred to a vast tent hospital erected overnight at the top of Corey Hill in Brookline, on September 9, 1918. It provided beds for several hundred flu-stricken sailors who had far exceeded the capacity of the Merchant Marine Hospital in Charlestown.

Further evidence of wide alarm about the epidemic can be inferred from an article published in the Boston Globe on September 23, reporting that a newly appointed committee of Boston and state health officials had, within hours of its first meeting, called Washington for medical aid. The national Red Cross office promised “to do all within possibility to assemble and hasten to Boston the nurses it could find available over the rest of the country.”

The article further noted the committee had agreed that “Boston school teachers might be drawn upon as assistants to nurses.” A voluntary registration system was instituted that very day at school department headquarters.

Read more about the 1918 influenza epidemic in eastern Massachusetts.

The flu news finally cracked the front page of the Patriot on September 28, 1918, though not as the lead story. Under the headline, “Epidemic Hits Belmont Hard,” the paper reported that the flu had “caused many deaths” and the governor had closed schools, churches, and theaters. Regular advertisers such as the Waverley Theatre, (“The Home of Clean Amusement”) announced temporary closures, but only until October 5; the closures were subsequently extended. The “Local Items” columns in the Patriot were full of reports of influenza.

The September 28, 1918 Belmont Patriot, featuring the headline “Epidemic Hits Belmont Hard.” Click to enlarge.

The October 5, 1918, issue of the Patriot reported on page one that the Board of Health, acting on state instructions, was closing public gatherings (also reported on September 28). A new item on page two under the heading “Influenza Bulletin” relayed recommendations issued by the Massachusetts Department of Health. Many are familiar: “Wash your hands . . . Don’t go to crowded places . . . avoid the person who sneezes.” Masks were recommended for nurses and doctors, along with instructions on washing and reuse, but not for the public.

Other recommendations don’t hold up so well, like the suggestion that nurses use “bichloride of mercury 1:1,000 or Liquor Cresol compound 1:1,000 for hand disinfection.” The “Local Items” columns on page three reported many cases of flu; however, there were also accounts of social get-togethers (the Reciprocity Club held a dinner, the Odd Fellows held their 75th anniversary banquet) and travel. Social distancing seems to have been unevenly practiced.

The October 12 Patriot announced on page one, “Influenza Scourge is on the Wane,” but warned in a sub-headline, “Too Early to Relax Vigilance and Precaution, Soda Fountains and Bowling Alleys Closed.” Schools, churches, and saloons also remained closed. The Board of Health forbade the sale of ice cream.

Another page one headline read, “Red Cross Does Effective Work in Checking Epidemic,” but noted the “unorganized condition” in which the volunteers had been pressed into service. Yet another item “strongly urges all citizens . . . to join the Belmont Hospital Aid Society in order to help provide funds for materials to be made into hospital supplies.” In effect, hospital supplies were hand sewn by volunteers from cloth they purchased.

The larger context of this exhortation was that Belmont relied on the Waltham Hospital to care for sick residents. In previous years, about 15% of the patients admitted to Waltham Hospital came from Belmont. By contributing cash donations and supplies, Belmont was buying future access to the hospital for Belmont residents. In 1910, the population of Belmont was 5,542, and of Waltham 27,834, though Belmont grew much faster over the ensuing decade than Waltham. The Waltham Hospital closed in 2003, after 117 years.

The theme of recovery continued in the Saturday, October 19, Patriot, with the news that schools, churches, and theaters would reopen the next day, October 20, because “On Tuesday only one new case was reported and on Wednesday none.” A story about the Belmont Hospital Aid Society noted:

“During the recent epidemic— in the month between Sept. 9 and Oct. 10—the Waltham Hospital has taken care of 254 cases of influenza. 140 of these developed pneumonia. This meant a great extra strain upon the limited capacity of the hospital and doctors and nurses were taxed to the utmost. For a few days there were 114 beds in use, the largest number in the history of the hospital.”

By November 2, the town was back to holding large public meetings, and the rest of November was relatively uneventful on the influenza front. Just a few cases were recorded in the “Local Items” columns (the end of the war was the big news). In the 1918 Belmont Annual Report, the Board of Health recorded a drop from 241 cases in September to 13 in November.

In summary, Belmont closed schools and businesses for only three weeks in 1918, and the Patriot consistently underplayed the severity of the epidemic. However, the 1918 influenza virus was different from SARS-CoV-2, with a shorter incubation time (interval from infection to illness) and apparently little dissemination by asymptomatic cases. Those factors made a three-week shut down (arguably) adequate, had it been complete. However, as noted in the “Local Items” columns, social activity never completely stopped, and influenza continued to smolder through November.

In the very last issue of the Patriot, December 28, 1918, the “Local Items” column reported flu cases in at least five families, while page four death notices, which usually did not include a cause of death, recorded the deaths of 6, 31, and 34 year olds. The last death was identified as a case of pneumonia following influenza. The 1918 Annual Report noted a jump of influenza cases from 13 in November to 222 in December, almost matching the September high. That is consistent with other parts of the country, where the flu epidemic did not end until 1919 or 1920.

The “Spanish” influenza

Spain was neutral in World War I, and consequently the press was free to report on the severity of the influenza pandemic in that country. King Alfonso XIII developed a severe case, and it became international news. The press in this country and elsewhere, by reprinting reports of the influenza outbreak in Spain, created the false impression that it was the origin or epicenter of the pandemic. In fact, other countries fared far worse.

The Emergency Hospital at Corey Hill

The “Local Items “column on page three of the September 21, 1918, Belmont Patriot noted that Belmont doctor William Hansen had been working night and day, and had been “ordered to the sailors’ hospital at Corey Hill” to care for influenza patients. The picture below shows the hospital in operation. As can be seen, staff wore masks. An article in the Boston Globe (September 29, p. 23) described the procedure:

“The safety of the attendants is due largely to the use of gauze masks. From the beginning every person who approaches a patient has been required to wear several folds of gauze over mouth and nose. A regular inspector of masks sees that everyone wears a mask and changes it every two hours. The inspector also is responsible for keeping a supply of masks always on hand and for the burning of the old ones.” Some municipalities, including San Francisco, passed ordinances requiring all citizens to wear masks. The exhortation went:

“Obey the laws, and wear the gauze./ Protect your jaws from septic paws.”

Treating influenza

On September 12, 1918, US Surgeon General Rupert Blue issued instructions on treating the flu. They were published in the Boston Globe and other major newspapers the following day.

“Treatment under direction of the physician is simple, but important, consisting principally of rest in bed, fresh air, abundant food with Dover’s powder for the relief of pain. Every case with fever should be regarded as serious and kept in bed at least until temperature becomes normal. Convalescence requires careful management to avoid serious complications, such as bronchial pneumonia, which not infrequently may have fatal termination. During the present outbreak in foreign countries the salts of quinine and aspirin have been most generally used during the acute attack, the aspirin apparently with much success in the relief of symptoms.”

Dover’s powder was a mixture of ipecac (an expectorant in low doses) and opium. Quinine, a natural product from the bark of the cinchona tree, is the forerunner of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, synthetically produced chemical analogs that some have suggested as treatments for COVID-19, however with very limited clinical evidence to date.

Aspirin was prescribed in massive doses (8 to 31 grams of aspirin per day), and has been blamed by some for iatrogenic deaths (Starko, Karen M., “Salicylates and pandemic influenza mortality, 1918–1919 pharmacology, pathology, and historic evidence”. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 49 (9): 1405–1410, 2009.)

The 1918 influenza pandemic in eastern Massachusetts

The 1918 influenza epidemic passed through the United States in a series of waves. The final wave in the fall of 1918 was the most lethal.

The spring 1918 wave, believed to have started on a military base in Kansas, primarily affected the usual victims of flu: the elderly and the very young. The fall wave, peaking in October, caused unprecedented sickness and death among younger, healthier people, apparently due to a mutation in the virus which elicited a harmfully exuberant immune response (a “cytokine storm” in contemporary medical parlance) in healthy people. The fall outbreak originated in Boston, according to contemporary accounts, spreading from sailors to the general population, and subsequently to the rest of New England and beyond. Between September and December 1918, there were more than 4,000 deaths in Boston. The Patriot did not provide a count for deaths in Belmont (however, Belmont Annual Reports contain all-cause mortality statistics.)

Influenza deaths: the official numbers

The Annual Reports of Belmont provide a numerically complete if colorless account of the epidemic, paralleling the stories in the Patriot. As the 1918 Board of Health report summarized the Belmont experience: “During the country wide epidemic of the early fall Belmont suffered comparatively lightly, a total of 593 cases being reported to the Board.” The population of Belmont in 1918 was 9,939, so about 6% were infected.

Belmont completely avoided the early phases of the epidemic: not a single case was recorded until September. Then cases rose sharply, fell sharply, and rose sharply again: 241, 117, 13, and 222 influenza diagnoses in the final four months of the year (see “Diseases by Months for 1918”).

Putting the influenza outbreak in a broader historical context, the 1921 Annual Report displays the incidence of communicable diseases for the previous 10 years (see page 294). Remarkably, no cases of influenza were reported in the years 1912 through1917. The number jumped to 593 in 1918, then 155 in 1919, 391 in 1920 and dropped to only 1 case in 1921, prompting the Board of Health to remark in 1922: “The total number of reportable diseases recorded during the year was 293. This total is the lowest since 1917. This tremendous decrease over the three preceding years is due for the most part to the decrease in influenza cases.” The Annual Reports contain overall mortality statistics, but the deaths are not categorized by cause. In the 1921 Annual Report (Vital Statistics, page 297), Belmont deaths for the years 1914 through1917 are 63, 68, 74, and 72, jumping in 1918 to 101, then declining to 75, 73, and 79 in the following three years. Thus about 30 deaths from influenza in 1918 can be inferred.

Belmont newspapers: the first draft of history

In 2015, Belmont Town Meeting appropriated $25,000 from the Community Preservation Act fund to digitize old Belmont newspapers. Here is a list of Belmont’s digitized newspapers and their publication dates. The records are searchable; however, the search interface is primitive. For this article, the more efficient search strategy was to go directly to the full-page images from the dates of interest in autumn 1918.

The earliest newspaper digitized is the Belmont Bulletin (March 8, 1890–February 26, 1898). It was succeeded by the Belmont Courier, the immediate predecessor of the Belmont Patriot. Following the Patriot’s one-year span, the Belmont Citizen started publication on March 29, 1919. The Belmont Herald debuted in January 1945. These two lasted until 1988, when they merged to form the town’s current weekly print newspaper, the Belmont Citizen-Herald.

Early Belmont history is also covered in the Cambridge newspapers, available in digitized form at the second url below. Four papers provided continuous coverage from 1846 until 2015, with the Cambridge Chronicle covering that entire 169-year stretch. (Note that when Belmont was created in 1859, it included the present Tip O’Neill golf course and surrounding neighborhood east of Grove Street extending to Fresh Pond. That territory was re-annexed to Cambridge in 1880 by an act of the state legislature.) For more information, see the Cambridge public library digital newspaper collection.

Belmont newspaper history

The Belmont Patriot was a one-year wonder. It commenced publication on January 5, 1918, and published its final number on December 28, 1918, six weeks after Germany’s surrender on November 11, 1918, brought World War I to a close.

Before the Patriot, from 1902 until April 1916 Belmont was a two-newspaper town (albeit they were weeklies, not dailies). The Belmont Tribune was published from 1902 until 1916. The Belmont Courier (1889–1917) lasted 18 months longer, until December 1, 1917, a victim of the war, which shrunk advertising budgets.

An item on the front page of the final issue of the Courier put its circumstances in context:

“For a number of years now, the publishers of the Belmont Courier have been pleased to issue a newspaper which the management has tried, in every way, to make creditable, not only to itself but also to the Town it was published for. There never has been a time when the paper has been self-supporting, but it has been continued until the time seems to have arrived when the support given to the Courier is not adequate, in our opinion, to justify the further publication of the paper under the present general business conditions. The cost of everything entering into the making of a newspaper, together with the policy of curtailment now prevalent throughout the country, has induced the management to decide to suspend publication, at least until after the war ….”

One month later, on January 5, 1918, the Belmont Patriot published its first number, under the aegis of the Belmont Committee on Public Safety, which offered the following account of its purpose in the lead article on page one:

“The Executive Committee of the Committee on Public Safety for the Town of Belmont is glad to grasp the opportunity offered by the first number of the Patriot, to express its appreciation of the way the various subcommittees of the Committee on Public Safety, the Red Cross, the War Relief and other kindred activities in the town, and the citizens generally have responded to the various calls for time, labor and money in 1917.… A silver lining to the clouds that envelop us is the unity, the brotherhood and the interdependence which the war is developing among our citizens.”

A more revealing account of Belmont newspaper history appeared in the December 14 issue of the Patriot, when the letters section on page two had become a forum for discussing what, if anything, was to follow the Patriot (which had already announced that December 28 would be its last number.) Mr. Albert Birch wrote:

“To Editor Belmont Patriot:

With reference to a Town Newspaper:

I take it as a matter of course that the intelligent desire a real newspaper. I do not think however that anybody would consider that the Courier or even the Patriot met or meets the demand of the average resident. The Courier was editorial-less a great part of the time and the editorials of the Patriot have been mostly high brow stuff…

Now my idea would be to publish the news of the town without fear or favor—yes, even publish the police court news. Why, I understand there are people in our town—mostly ladies—who think there is nothing but wholly good in it. Let us know about the hearings the Selectmen give. I was at a hearing a few weeks ago of a number of property owners from around Waverley who were kicking like fury about being soaked for betterments. And yet no information or editorial comment was given in the Patriot.… And we want the Assessors discussed, the Highway Dept discussed, the Electric Light, the Police, the Town Council, the Water Board, the Town Treasurer Dept and all and everything discussed and criticized and explained in an informative, intelligent and constructive manner.

The present control of the Patriot makes it seemingly impossible to do what a real Town paper should do…

Why, Mr. Editor, the Town is seething with lively subjects for discussion but so long as we insist in meeting together in a mutual admiration style it will be impossible for us to progress and improve, and support a Town Paper and properly do all we ought.”

And so forth.

The Belmont Patriot

The masthead of the Patriot shows that its “Editorial Rooms” were located in the Homer School (later the Town Hall Annex and today the restored Homer Building), further evidence of what an unusual operation it was. A one-year subscription cost 50 cents and a single issue cost 3 cents. While that seems inexpensive today, when an issue of the Belmont Citizen Herald costs $2, the Boston Globe, a much fatter paper, cost 2 cents per issue in 1918.

Local Items Column, September 7, 1918 vs. September 21, 1918

1918: Belmont was still a farm town

The war environment engendered a strong sense of community. One example is the community gardens (or war gardens), overseen by the Committee on Food Production and Conservation, a subcommittee of the Belmont Public Safety Committee (publisher of the Patriot). The September 7 paper previewed a large upcoming War Gardens Exhibition at Town Hall, noting that 957 jars of canned food had been produced by the Community Kitchen in the previous week, bringing the total for the year to 9,000 jars. The article continued:

“Robert Trask, a graduate of the Cornell University College of Agriculture, has recently made an inspection of community kitchens in Massachusetts. He reports that the Belmont kitchen has the best equipment and best management of any he has visited. He further says that Belmont prices are the lowest.”

Attendance at the farm exhibition was estimated at 600 to 800 in the September 14 paper. Awards were presented for the best produce in each of 38 categories (first, second, and third place), making a total of 114 prizes, plus five honorable mentions. (When you next hear the complaint that “everyone gets a trophy,” you will know that it has been that way for quite a while.)

Belmont odds & ends

- The Patriot was full of advertisements, cartoons, and stories exhorting citizens to buy war bonds, called Liberty Loans. World War I was funded with cash. (Modern monetary theory had not been invented.) In the fall of 1918, the fourth campaign for Liberty Loan bonds was wrapping up, and Belmont’s Liberty Loan Committee, a group of over 100 citizens divided into 31 neighborhood districts, set a goal of $650,000, which was exceeded by over $43,800. For context, the town budget in 1917 was less than one third that amount, $225,304.73 (source: December 1, 1917, Belmont Tribune).

- 1918 was the last year the Red Sox won the World Series before their 20th-century run of glory. They finished off the Chicago Cubs in six games, the final played on September 11 at Fenway Park. The star of that 1918 team was, of course, Babe Ruth. The Waverley Cubs baseball club had a formidable Babe of their own, as a short item in the September 14 Patriot reports:

“Cubs Win Two Games

In a well played game last Saturday afternoon on the Town Field, the Waverley Cubs defeated the Park A.C. of Watertown 9 to 0. ‘Babe‘ Melanson, the pitcher of the Cubs, struck out 19 men and allowed only 1 hit.”

The debut issue of the Patriot contained an item called “Roll of Honor,” listing 93 Belmont men enlisted in the Army, Navy, or Marines. Among them: James Watson Flett, whose father George was at the time chair of the Board of Selectmen. Flett would go on to win election as Belmont’s representative in General Court in 1922, and subsequently had a long career as a selectman himself.

For even more records of Belmont’s 1918 influenza epidemic, scans of the Belmont Patriot, and other historic documents, check out the Belmont Citizen Forum’s Google Drive folder about the influenza epidemic.

Vincent Stanton, Jr. is a director of the Belmont Citizens Forum.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.